Traditionally, men were appointed lighthouse keepers. Along all of our Nation’s waterways, women were only assigned to the position following the death of their keeper husband or that of another male relative in the same position. However, if the widow remarried, on the order of the Light-House Board, she was immediately removed from the position, and her new husband was appointed to the post!

The first women to be designated as lighthouse keepers were Irish nuns living in the seaside town of Youghal, County Cork. In its early history, the Vikings, who were great sea traders (and raiders), had established themselves at Youghal. With its close access to the Atlantic, the community became an active port. However, over time the rock reefs, which were scattered throughout its approaches, contributed to numerous shipwrecks. Around 1202, to ensure maritime safety, local leaders erected a small lighthouse on the harbor’s west bank. To assure the reliability of its keepers, nuns of the nearby St. Anne’s Convent were selected for the position. Every evening, a nun climbed the tower to light its navigational beacon. The nuns continued to maintain the lighthouse and its beacon until 1542 when their convent was closed. During their time as lighthouse keepers, St. Anne’s nuns were said to have participated in the rescue of some shipwrecked sailors.

U.S. Coast Guard historical records list 175 women who were appointed as lighthouse keepers. The first was Hannah Thomas who served from 1776 to 1786 at Plymouth Massachusetts’s Gurnet Point Light. With the onset of the Revolutionary War, her husband keeper joined the battle for Boston. Later, during the battle of Quebec, he succumbed to smallpox, which had spread through the Continental Army.

Gurnet Point Light consisted of twin towers, each equipped with two lanterns. In addition to her lighthouse duties, Hannah raised her three children and tended to the farm, which stood next to the lighthouse. When she retired in 1786, Hannah hired a local man, Nathaniel Burgess, to serve as lightkeeper. Several years later, he was officially appointed to the post.

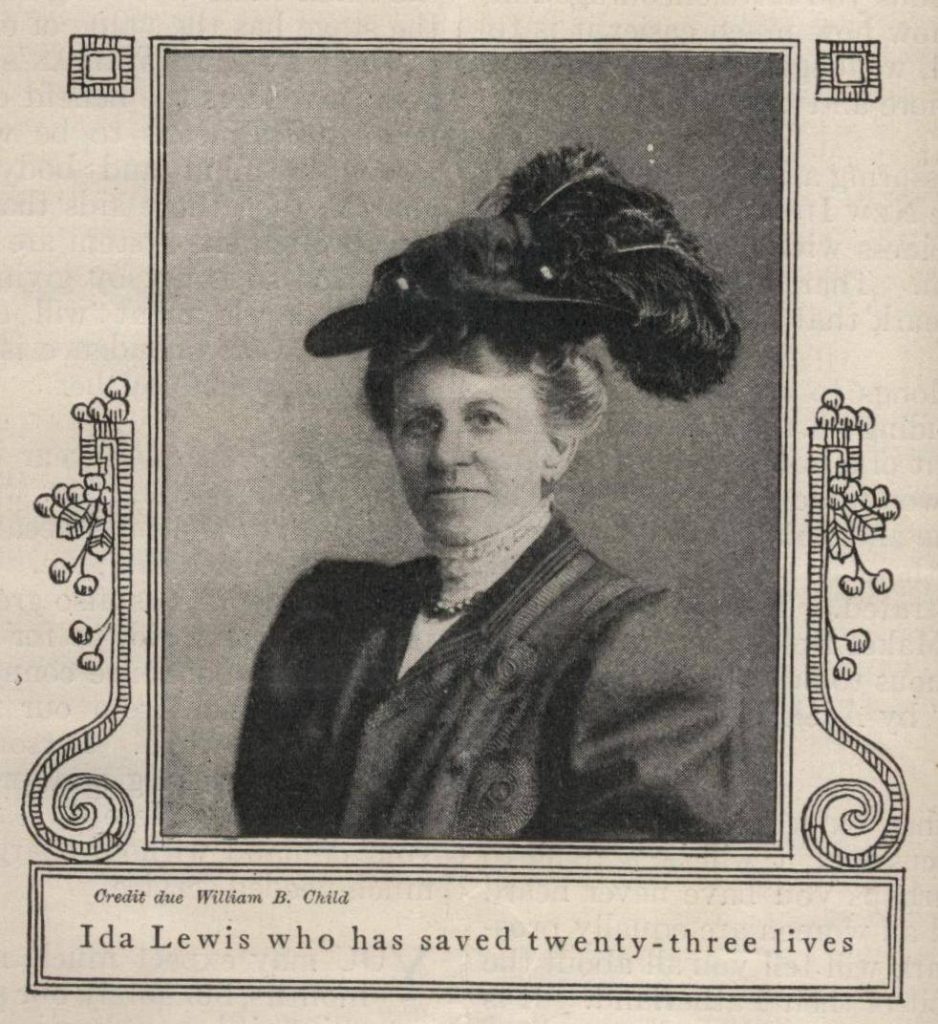

Similar to most men who kept the lights, women keepers did not hesitate to go to the aid of sailors in distress. The Nation’s most famous keeper-heroine was Ida Lewis. In 1853, Ida’s father Hosea was appointed keeper of Newport Rhode Island’s Lime Rock light station. Standing about 250 yards offshore, the island’s navigational beacon consisted of a small lantern and a shed that served for storing supplies and a keeper’s shelter during storms. Each day, Hosea rowed out to the rock to maintain its beacon, while his family lived ashore. In 1855, the Lighthouse Board directed that a permanent dwelling be built on the island. A couple of years later, the entire family was finally able to move into the square, two-story building. The lighthouse’s lantern room, extending out from the house, was equipped with a six-order Fresnel lens. The lantern was accessible from the dwelling’s second floor.

Four months after moving into their new dwelling, Hosea suffered a severe stroke. Unable to continue his lighthouse duties, Ida’s mother took over along with his care and that of a seriously ill daughter. Still very young, Ida aided in the care of the beacon and other household duties.

As the eldest of four children, Ida quickly learned how to handle the station’s heavy rowboat. Even as a young teenager, she rowed to shore to get supplies and each school day, transported her siblings back and forth to Newport. However, she was so involved with the lighthouse duties that she was never able to participate in any form of schooling. When just 12 years old, she spotted four young men who had capsized their sailing vessel near the lighthouse. Making her way out to the disabled boat, she aided all of them up and over the stern of her rowboat and transported them back to land.

Following the death of her father in 1873, her mother was appointed keeper. By that time, however, Ida already had taken over all of the lighthouse responsibilities. About five years later, her mother succumbed to cancer and Ida was then officially appointed keeper. Throughout her time at the lighthouse, Ida was credited with saving 23 lives. Her most famous rescue occurred on March 29, 1869.

During a light snowstorm, two soldiers enlisted a young lad to transport them to Fort Adams aboard his small boat. As they made their way from Newport to their destination, wind-driven waves rocked the boat until it capsized. All three were thrown into the frigid waters. The two soldiers managed to cling to the boat, but the lad quickly slipped below the surface. Observing the accident from the lighthouse, Ida launched her rowboat and made it out to the vessel. With the help of her younger brother, they were able to haul in the beleaguered soldiers and take them back to the lighthouse.

After her exploits were described in the press, a large number of people made their way to the lighthouse to meet her. These included General William, Tecumseh Sherman and President Ulysses Grant. Later, she was called “The Bravest Woman in America.” In 1924, the Lime Rock Light was renamed the Ida Lewis Light.

During the War of 1812, British troops frequently raided coastal communities. In September of 1814, Scituate Light Keeper Samuel Bates left his two daughters, Rebecca and Abigail in charge of the station while he and the rest of the family went ashore for supplies. At some point, the girls noticed that a British ship had dropped anchor just offshore and launched two boats of “red coats.” Rebecca picked up her fife and Abigail her drum. Then, making their way toward the beach, they hid behind trees and played “Yankee Doodle” as loud as they could. Thinking that they were about to be challenged by a large contingent, the British quickly retreated to their ship and sailed off. The young ladies were later called the “Lighthouse Army of Two.”

Kate Moore was barely 12 years old when she took over most of the lighthouse duties at Connecticut’s Fayerweather Light. Her father, Keeper Stephen Moore, had been incapacitated during an accident. Each evening, Kate lit the eight oil lamps, which had to be replenished at intervals throughout the night. During storms, the wind could blow them out, making it necessary to remain in the tower all night long. Following the death of her father in 1871, Kate was named keeper. During her 61 years at the lighthouse, Kate was credited with saving 21 lives. However, unlike Ida Lewis, she never received the same attention for her heroism.

Fayerweather had a second female keeper, Mary Elizabeth Clark. She assumed the position following the keeper’s husband’s death on March 14, 1906. Two months later, John Davis was appointed keeper. He remained at the lighthouse until it was discontinued on March 3. 1933.

There were many other women lighthouse keepers who also became heroes. Just like the men who served as keepers, “they gave their all.