Each month, an interesting aspect of the world’s oldest continuous maritime service will be highlighted. The men and women of the United States Coast Guard follow in the fine tradition of the brave mariners who have served before them. As sentinels and saviors of the seas, the United States Coast Guard proudly continues its commitment to honor, respect & devotion to duty to maintain their vigil – Semper Paratus.

The Yamacraw’s Loss

The tanker Louisiana was bound from Tampico, Mexico for Claymont, Delaware when it ran aground on Little Gull Shoals off of Ocean City, Maryland in the early morning hours of March 4, 1917. Though a thick fog blanketed the bulk of the tanker, a Coastguardsman on patrol discovered her at twenty minutes past eight o’clock in the morning. The patrolman raced back to the station and updated the keeper and they notified the district superintendent. The keeper of the No. 146 requested assistance from the No. 145 station and at roughly ten o’clock in the morning, the keeper and three surfmen launched a surfboat into the swells. Despite the conditions, the lifesavers were able to come alongside the tanker and hail the master. The master of the tanker Louisiana thanked the surfmen for their offer of assistance and asked only one favor. The master tossed a message in a bottle to the surfmen that contained a message for issuing via telegram to the ship’s owners. The keeper and surfmen asked again if the Master wanted to have him and his crew removed. The Master thanked them for their efforts but waved them off. The master only requested that the message be sent to the owners for tugs to arrive on the scene to pull them free from the shoal. The surfmen acknowledged the request and returned through the breakers for the beach.

Five hours later, the master of the tanker Louisiana had changed his mind based on the changing weather conditions. The November Charlie signal flags were spotted by the lifesavers on the beach who again set out for the tanker in the surfboat. Waves had increased and the tanker was being severely beaten. The swell had increased from the southwest and winds were strengthening from the east-northeast. Heavy seas were breaking over the tanker from aft forward and the outgoing swells were causing strong suction under the tanker’s bow. The surfmen braved the harrowing seas and were able to get alongside once again. The surfmen were prepared to lighten the tanker of its master and crew but were surprised when the master formally requested again, a tugboat or a cutter to assist them in clearing the shoal. As the surfmen maneuvered through the breakers the lifeboat was swamped by a huge wave. One of the surfmen was thrown out of the boat and was slightly injured. Pulled back into the lifeboat, the surfman was brought back safely to shore with his shipmates.

Before the tanker Louisiana had run aground, the United States Coast Guard Cutter Yamacraw, short nearly forty percent of her crew on the evening of March 3, 1917, set out from her dock in Norfolk, Virginia to answer a radio distress call issued by the British steamship Strathearn which reported that they were ashore at Metomkin Inlet. Though he was short-handed, the commanding officer of the cutter wanted to gain the advantage of reaching the inlet an hour before high water.1 As the U.S.C.G.C. Yamacraw set out on her quest to locate the stranded Strathearn, a new distress call was heard over the radio. The American flagged tanker Louisiana was hard aground. The U.S.C.G.C. Yamacraw altered her course as it was ascertained that the Strathearn was in a much better position than Louisiana. Due to an erroneous position transmitted from the tanker, it was not until after eight o’clock in the evening when the U.S.C.G.C. Yamacraw located the stricken tanker teetering in the swells.

The captain and officers took stock of the increasing winds and the deteriorating weather and sea conditions. Though the swells and winds were not ideal, the men agreed that the conditions were not beyond their abilities of the men to affect a rescue. While the U.S.C.G.C. Yamacraw lay approximately half a mile away in deeper water, the coastguardsmen signaled for Louisiana to discharge oil to attempt to calm the seas. As the oil was spread over the water, the cutters surfboat was lowered to the water’s edge. In charge of the surfboat was Gunner Ross Harris. He was joined by Master-at-Arms R.J. Grady, Quartermaster M.L. Kambarn, Seaman G.V. Jarvis, and five ordinary seamen, M.L. Austin, D. Fulcher, R.L. Garrish, R.E. Simmons, and T.L. Midgett. The surfboat eased its way toward the tanker. Once alongside, Gunner Harris tied off to the painter line from the tanker’s rail. As one of the crewmen from the tanker was climbing down to the surfboat, a wave washed across the decks of the tanker. The wall of water swept the crewman off of the rope ladder and into the surf. The surfboat slammed against the hull of the tanker and capsized. The ten coastguardsmen were thrown into the swirling maelstrom.

Faint cries for help could be heard aboard the cutter. The cutter’s coastguardsmen quickly weighed its anchor and maneuvered closer to the stricken tanker. As the cutter neared, coastguardsmen on deck spotted Master-at-Arms R.J. Grady holding onto a lit buoy. Grady, his hands nearly frozen to the buoy, dove into the water and began swimming towards the cutter. Meanwhile, steerage cook J.J. Kennedy tied himself off to a line and leaped into the frozen sea and began to swim toward Grady. J.J. Kennedy was able to grab Grady, but in the icy waters, he lost his grip on his shipmate. Grady slid under the pitching hull of the cutter and out of sight. Moments later, 2nd Lieutenant W.J. Keester, who had also tethered himself to a line secured to the cutter’s gangway, spotted Grady as he appeared on the other side of the hull. He reached out and grabbed Grady. Seconds later, another wave crashed against the cutter. Lieutenant Keester also lost his grip. Master-at-Arms Grady disappeared into the darkness of the night.

Lowered into a dinghy, sixteen-year-olds William R. Hogarth and J.A. Dugger, set out to retrieve Grady. Their efforts were fruitless. Spotting R.E. Simmons, one of the coastguardsmen from the capsized surfboat, the boys rowed through the seas to the lit buoy and attempted to get him into the dinghy. Simmons, exhausted by the elements, was unable to get pulled into the dinghy so the boys quickly lashed him to the side of the dinghy. The boys began rowing the dinghy back toward the cutter but the swells and current proved too strong. The dinghy suddenly struck several stakes of a fishing pound and capsized. The two boys and Simmons were tossed into the surging seas. Hogarth was able to catch his breath and floated free. Dugger and Simmons were not as lucky. They both slipped into the darkness of the abyss.

Aboard the cutter, it was decided to launch the whaleboat. Under the command of Boatswain Hermann Fiedler, the whaleboat was launched to try and recover the shipmates lost from the first surfboat and the dinghy. Joining Fiedler was Electrician 3rd class Belton Miller, Boy 1st Class George L. Wynn and Boy 2nd Class J. McWilliams. The Coastguardsmen searched the area but found no one. With the deteriorating conditions continuing, the officers of the cutter signaled Boatswain Fiedler to not attempt to return to the cutter and to instead anchor outside of the breakers. Boatswain Fielder and his crew took stock of the conditions and decided to head through the breakers to the safety of the strand. Meanwhile, the cutter remained on station scanning the waters for her missing shipmates and then eventually retreated to deeper water a few hours later when it was clear that her shipmates were nowhere to be found.

As the night turned into the early morning, sea conditions improved. At first light, the cutter returned to the tanker and surrounding waters in a vain search for the missing. None of the men were located. With the improved weather conditions, the tanker Louisiana was able to extricate herself from the shoal and into deeper water. Ten coastguardsmen and one member of the tanker Louisiana’s crew had been lost in the failed rescue attempt. It was a dark day for the service.

A Board of Inquiry was held to investigate the incident and the subsequent loss of life. The board concluded that “the loss of life was entirely unavoidable, and that no blame attaches to any person in the Coast Guard on account thereof. On the contrary, it is shown that personnel of both cutter and stations did everything in their power to render assistance and save lives throughout the incident. The members of the inquiry board also recommended that the service’s Lifesaving Medal (2nd class) be awarded to Steerage Cook J.J. Kennedy for his heroic efforts in trying to save Master-at-Arms Grady.

Commendations of the conduct of the coastguardsmen from the Yamacraw continued. For the members of the initial surfboat under the leadership of Gunner Ross Harris, the board noted their “conspicuous gallantry in promptly and eagerly responding to the urgent calls from Louisiana for assistant and making an attempt to rescue the crew of that vessel.” For Boy 1st Class J.A. Dugger “for zeal and devotion to duty in responding eagerly and fearlessly to a call for assistance and giving up his own life in an attempt to save the lives of his shipmates” and to coastguardsmen in the dinghy and whaleboat for their “zeal and courage in their efforts to rescue their shipmates who were struggling in the water.” For the service, the loss of life of so many of one cutter’s crew was monumental.

The board members concluded in their report that they were “impressed by the fine examples of bravery, fidelity to duty, and self-abnegation shown to have been exhibited by those to whose lot it fell to take part in this unfortunate and tragic event. The department commends these officers and men in the highest terms.” As further noted by William G. McAdoo, Secretary of the Treasury in his Special Order No. 15, issued on April 2, 1917, and to be read at a general muster at each unit and aboard all vessels in the service’s fleet, “True to the noblest traditions of the sea, faithful to their highest trusts, even to the sacrifice of their lives without thought to self, those who perished went voluntarily on the errand of mercy, that they might save the lives of their fellow men. The survivors, no less true to these noble traditions, and undismayed by the disaster which had overtaken their comrades, met the situation with a spirit of bravery and determination which calls for the highest encomiums. To them, the department extends its felicitations and believes that the experiences of the occasion will serve as an inspiration to even greater endeavors and accomplishments. Events like these, sad as they are, lend enduring luster to the service and strengthen still further its century-old traditions, of which our Government has the right to be proud.”

The valiant efforts of the coastguardsmen aboard the U.S.C.G.C. Yamacraw in their attempt to assist the crew of the tanker Louisiana were a stark reminder to the service and the nation of the dangerous and sometimes deadly nature of the work of the United States Coast Guard. The selfless acts displayed by the coastguardsmen demonstrated the service’s long-standing tradition of assisting those in need, even if it meant sacrificing one’s own life for the cause. The ten coastguardsmen lost in the tanker Louisiana rescue efforts will forever remain as testaments to the service’s rich history and as examples of coastguardsmen and their tireless dedication to their duty as sentinels and saviors of the seas.

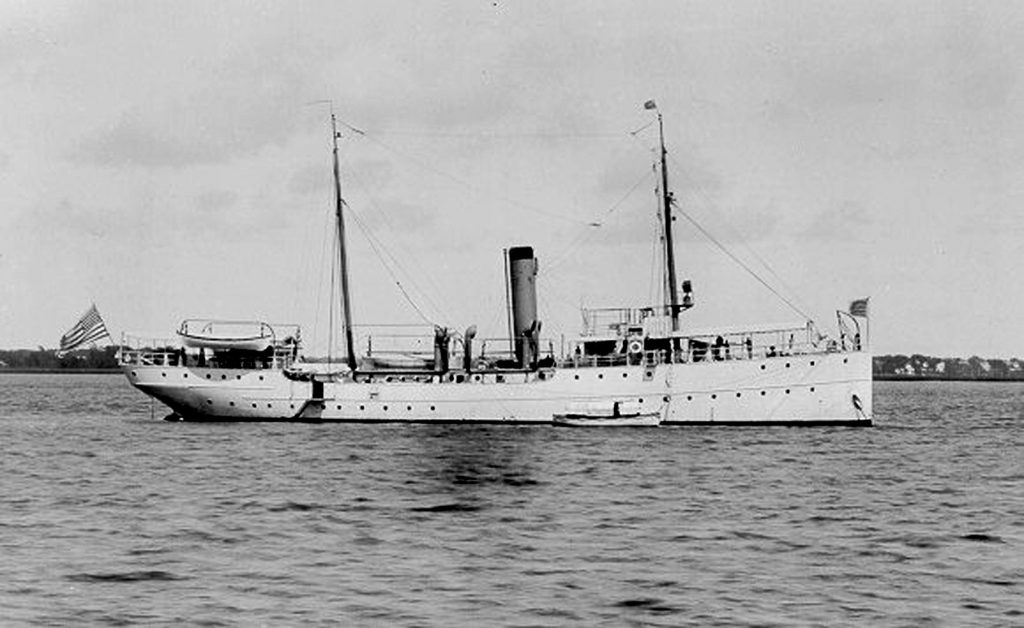

1 Forty percent of the cutter’s enlisted force was on liberty at the time of departure. Her normal compliment would have been eight officers and sixty-five enlisted personnel. The Yamacraw was a “first-class cruising cutter” and had been built by the New York Shipbuilding Company of Camden, New Jersey. Shew as one hundred and ninety-one feet, eight inches in length, with a beam of thirty-two feet, six inches and a draft of thirteen feet. She was powered by a triple expansion steam engine that was capable of providing a top speed of fourteen point one knots with a cruising range of thirty-five hundred nautical miles at economical speed. She was commissioned on May 17, 1910. After the war was declared with Germany, she was “temporarily” assigned to the U.S. Navy’s Sixth Patrol Force. On July 19, 1917, she was transferred to the Fifth Naval District until selected for overseas convoy duty. During her wartime service, she was responsible for escorting over seven hundred ships, credited with severely damaging/possibly sinking an enemy submarine and cruised roughly thirty-six thousand miles. After the cessation of hostilities, the Yamacraw returned to her peacetime missions out of her home port of Savannah, Georgia. She participated in the International Ice Patrol and was instrumental in southern waters during the era of Prohibition. She was decommissioned on December 11th, 1937 at Curtis Bay, Maryland