Each month, an interesting aspect of the world’s oldest continuous maritime service will be highlighted. The men and women of the United States Coast Guard follow in the fine tradition of the brave mariners who have served before them. As sentinels and saviors of the seas, the United States Coast Guard proudly continues its commitment to honor, respect & devotion to duty to maintain their vigil – Semper Paratus.

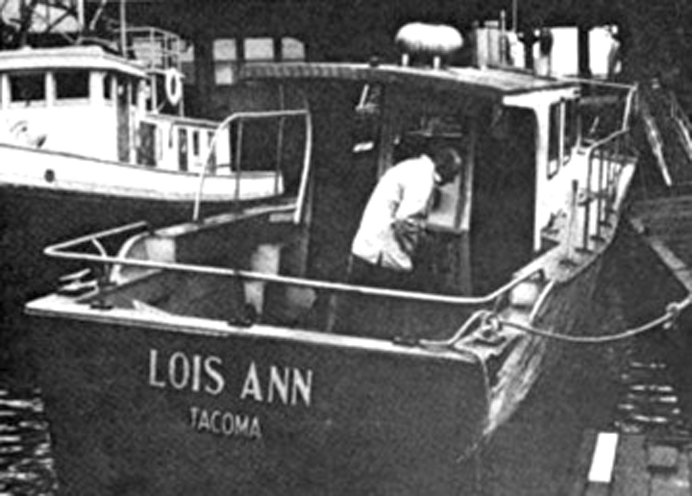

The Loss of the Lois Ann

The Lois Ann had been a labor of love for Walter A. Johnson. His family and friends were excited at the occasion. Walter stood aboard his creation and rested one of his hands on his son Rolf’s shoulder. Mrs. Johnson, Walter’s wife, smiled as she sat down on the transom. A total of eleven had joined Walter for the maiden voyage of the Lois Ann. Johnson had decided to build a sport fishing boat capable of carrying twelve passengers. His plan was to run a charter business out of Westport, Washington. Utilizing the hull of a war-surplus United States Navy LCVP, Johnson had dismantled the craft so he could utilize the frames and planking as the template for the design. With the assistance of a family friend, a former United States Navy hull inspector, Walter then designed and built a new bow.

The Lois Ann, upon completion, was forty-two feet, five inches in length, with a beam of ten feet, four inches, and a draft of three feet forward and three feet, one inch, aft. She was powered by a one hundred and sixty-five horsepower General Motors diesel engine, Model Six Seventy-One. Nearing completion, Johnson applied for a United States Coast Guard inspection. A Coast Guard inspector visited the craft and completed some tests including a hose test of the bulkheads separating the fuel tank space from the berthing and cockpit. Additionally, the hull fittings, engine installation, and associated piping were all deemed in compliance with the regulations. Despite efforts by the United States Coast Guard to schedule a continuance of the vessel’s inspection, Johnson indicated that he wanted to install a radio and finalize up the outfitting of required gear prior to the request for final inspection and certification. The final inspection never took place.

On April 26, 1959, roughly a month after the United States Coast Guard’s attempt to finalize the inspection and certification, Johnson, his family and guests departed from Tacoma, Washington on a trip to Seattle, Washington. Johnson was planning on calling on the ABC Charter Agency to arrange for possible employment for him and his boat for charter trips. The celebratory nature of the voyage quickly deteriorated as the weather called for overcast conditions and intermittent squalls. Winds increased and the Lois Ann was faced with a following sea. Rolf, Johnson’s son, was on the weather deck near the bow with Janet Wick when he noticed water collecting in the aft end of the cockpit. He immediately pointed out the condition to his father who turned the bow into the wind. The stern began to settle with water entering the freeing ports. The engine sputtered and Johnson had no power. He quickly passed word to everyone to don their life jackets. Johnson went to the stern to try and investigate what had happened. Meanwhile, his wife, while exiting the cabin, slipped and fell as she was attempting to get to the bow. Johnson alighted to assist her. Within a matter of moments, the Lois Ann had developed a significant starboard list. Someone passed twenty-month old Rodney Tayet, wrapped in a life preserver, through one of the open cabin windows. Rolf spotted the baby in the water and dove in to save him. Seconds later, the Lois Ann rolled to her starboard leaving only a few feet of the bow remaining above the surface. Mrs. Johnson, Rolf, Janet Wick, Frithjof Tayet, and Johnson had all been thrown into the chilly waters off of Alki Point.

Gerald Hoeck, a resident of Alki Point, witnessed the boat sinking and immediately sprang into action. Hoeck ran next door to summon his neighbor, Roy Anderson. Anderson quickly called the United States Coast Guard to alert them of the distress. Within five minutes, the men set out toward the half-sunken boat aboard a twelve-foot aluminum boat. Heads bobbed in the water. The small ad-hoc rescue boat got on scene and took immediate action. Johnson, who had taken the infant from his son, was standing on the floating bow section and was holding the infant Tayet in his arms. The rescuers threw a life jacket to Rolf and pulled Janet Wick into their boat. They then assisted Mrs. Johnson. Trithjof Tayet had been thrown into the water and was seen by Rolf and the others clinging to a tire. Seconds later, he simply disappeared. As Hoeck and Anderson began assisting the survivors, another boat, a cabin cruiser skippered by Robert Kronberg arrived on scene. Kronberg assisted Rolf, Rodney Tayet, and Mrs. Johnson from the water. There were seven unaccounted for from the original party of twelve. A helicopter passing overhead noticed the situation and swung in low to offer aid. Mr. Johnson was pulled from the Lois Ann by the pilot, a United States Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel, with the use of a rescue sling from the helicopter T-302.

Hoeck and Anderson began to head to shore to get their survivors to medical attention. As they were cautiously heading shoreward, they passed the CG-40422. Word was quickly passed to the Coastguardsmen of the situation and how many they had pulled from the water. The CG-40422 then raced to the stricken boat. Within moments, Seattle Harbor Patrol Boat Number 7 arrived on scene. The Coastguardsmen and harbor patrol officers quickly took the Lois Ann in tow and maneuvered her into shallow and calmer waters south of Point Williams. Gaining access to the cabin, the rescuers found the missing passengers – Mrs. Frithjof Tayet, Janna Lyn Tayet, Lois Ann Johnson, and Mr. and Mrs. Reuben Torgerson – had all been trapped in the cabin. None survived. After the bodies were removed, the Seattle Fire Department arranged to pump out the Lois Ann. While preparing for dewatering, a fireman discovered that the union forward of the T in the supply line to the raw water-cooling pump was uncoupled.

Despite the efforts of two United States Marine Corps helicopters, a helicopter and fixed wing asset from the United States Coast Guard Air Station at Port Angeles, Washington, and a host of United States Coast Guard and other local agencies boats, Martin Tayet was never found. The subsequent investigation into the tragic end of the Lois Ann highlighted that the cause of the casualty was the “flooding of the area beneath the cockpit deck due to the ingress of water through an uncoupled union in the raw water supply line to the heat exchanger.” The passengers, in the cabin had little chance of survival. When Johnson altered his course into the wind, “the vessel capsized due to the effect of the sea on the vessel in its condition of reduced stability.” When the Lois Ann capsized, water “rushed through the open starboard door quickly filling the cabin and berthing spaces and submerging the passageway to the forward escape hatch.” The investigation also outlined that the “lack of experience of the operator in the operation of vessels of the type and size of the Lois Ann contributed to the casualty insofar as his failure to realize the after compartment of his vessel had flooded until it was too late to take effective corrective measures.”

The loss of family and friends during the capsizing of the Lois Ann highlights the importance of United States Coast Guard inspections. It is possible, had the final inspection taken place, that the loose connection might have been noticed. The lack of a final inspection coupled with an inexperienced boater had ended in tragedy. Thankfully, due to the quick action of Good Samaritans working in tandem with United States Coast Guard, United States Marine Corps, and Seattle Harbor Patrol personnel, five of Johnson’s passengers and family survived the maiden voyage of the Lois Ann. Boaters are reminded of the importance of obtaining and ensuring certification and inspections by the personnel of the United States Coast Guard and United States Coast Guard Auxiliary. It the dedication to assisting boaters and their family and friends in helping to ensure safe boating that the men and women of the United States Coast remain true to their profession as sentinels and saviors of the seas.

Sources:

Brown, Ronald J. “U.S. Naval Aviation Designators.” Flyingleatherneck.org, December 2013.

Rawlins, Eugene W. Marines and Helicopters 1946-1962. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., 1976.

The Skipper.

“Casualty Report,” September 1960.

United States Coast Guard. “Commandant’s Action on Marine Board of Investigation; Flooding of the motorboat Lois Ann, Puget Sound, 26 April 1959, with loss of life,” United States Coast Guard Headquarters, Washington, DC. 9 September 1959.