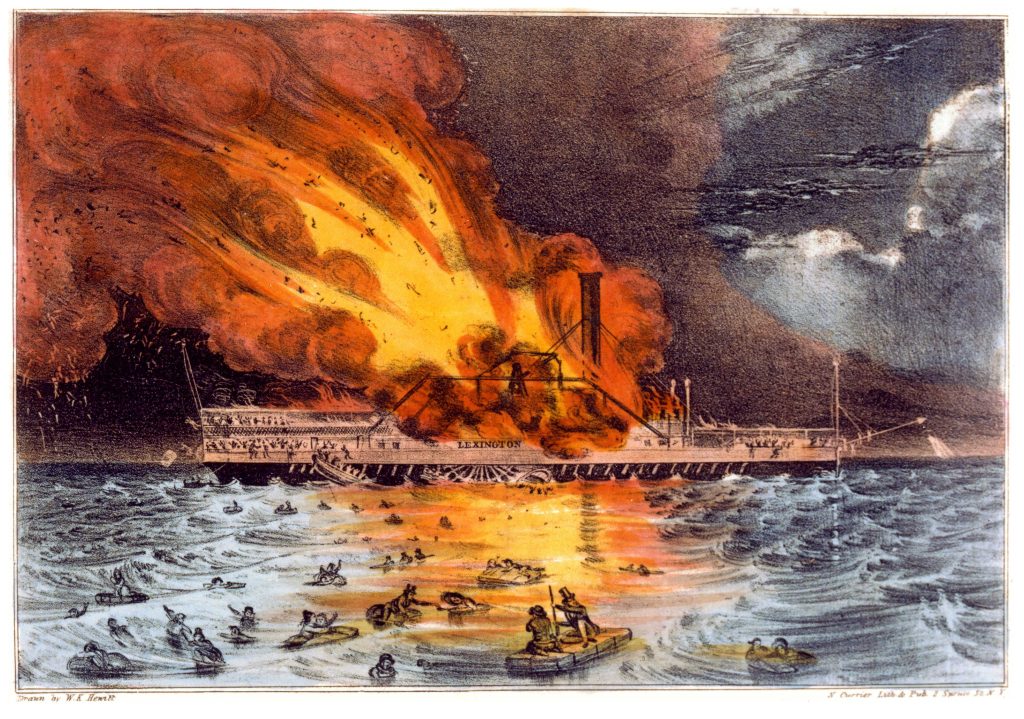

The following is an excerpt from The Sinking of the Steamboat Lexington on Long Island Sound by longtime Boating World contributor Bill Bleyer that will be published May 1 by The History Press.

On Monday, January 13, 1840, after boarding passengers and loading cargo, including nearly 150 bales of cotton placed on the main deck, the revolutionary vessel designed by Cornelius Vanderbilt eased away from the New Jersey Steam Navigation and Transportation Company pier at the Battery in Manhattan at 4:00 p.m. The temperature was four degrees.

The list of passengers included two prominent comedic actors from Boston. Charles Follen was a professor of German literature at Harvard College and a minister. Mary Russell had been married the day before in New York and was returning to her New England home without her new spouse to break the news to her parents. Three members of the family of recently deceased Henry A. Winslow, including his widow, Alice, were accompanying his coffin stowed in the hold for burial in Providence. Many were traveling for business. Adolphus Harnden of Harnden’s Express was the younger brother of William Frederick Harnden, founder of a nineteenth-century forerunner of FedEx. He was transporting gold coins amounting to $14,000 and silver coins amounting to $11,000 for the Merchants’ Bank in Boston.

There were also several ship captains traveling as passengers, including 24-year-old Chester Hillard, who would play a critical role in the events that followed.

Stephen Manchester, the pilot, was steering the steamboat when the fire was discovered. One of three surviving crewmembers, the Providence, Rhode Island resident was a witness at the seventh day of the inquest into the disaster.

Manchester testified that he was in the wheelhouse when…about 7:30 o’clock, someone came to the wheelhouse door and told me the boat was on fire… My first movement was to step out of the wheel-house and look aft; saw the upper deck burning all around the smoke pipe… I returned into the wheel-house and put the wheel hard-a-port to steer the boat for the land [Eatons Neck]… when something gave way, which I believe was the tiller rope…and at the same time the smoke came into the wheel house…I then called to them on the forecastle [by the bow] to get out the fire engine and buckets; the engine was got out, but they could not get at the buckets, or at least I only saw a few.

I went to the lifeboat…. I called to those at the forecastle [on the deck below] to pass a line to make fast to her, which they did, and we fastened it to her bow…to prevent the life boat going under the [paddle] wheel, and it was made fast. I cut the lashing, and told them to launch the boat. I … found it was not fastened to the steamboat. I told them to hold on to the rope, but they all let go one after another; the engine was still going…

Chester Hillard testified at the inquest that “When I got on deck I discovered the casing of the smoke pipe on fire, and I think a part of the promenade deck was also on fire. There was a great rush of the passengers, and much confusion.”

Moving up to the promenade deck, Hillard saw that one of the two lifeboats had been filled by panicked passengers. Crewmembers were in the process of lowering it—despite the ship still forging ahead at thirteen miles per hour, making it virtually impossible to launch them successfully because the rushing water would inevitably flood and capsize them.

“They seemed to be stupidly determined to destroy themselves, as well as the boats which were their only means of safety,” Hillard stated. “I went to the starboard boat, which they were lowering away; they lowered it until she took the water, and then I saw some one cut away the forward tackle [block and tackle for lowering the lifeboat].…The boat instantly filled with water, there being at the time some twenty persons in her; the boat passed immediately astern.” He went to the port side of the vessel and watched as the other boat full of passengers was lowered, filled with seawater and then drifted astern.

With flames burning up through the promenade deck, Hillard testified, “I thought it was time for me to leave.”

It was now about twenty minutes after the first alarm of fire had been sounded and five minutes since the engine had stopped. Hillard added,

I then recommended to the few deck hands and passengers who remained, to throw the cotton overboard. This was done, myself lending my aid…. There were perhaps ten or a dozen bales thrown overboard.

Charles B. Smith of Norwich, Connecticut, one of the four firemen stoking the boilers, testified at the inquest that … he rushed to where the fire hose was located and opened the valve. But the flames kept him away from the nozzle end of the hose, so it was useless.

Second Mate David Crowley, the fourth and last man rescued, did not testify at the inquest because of the precarious state of his health, but he did provide accounts to the newspapers, as quoted below:

Captain [George] Child, in reply to an inquiry from some of the passengers of what was to be done, replied, in a collected manner, “Gentlemen, take to the boats… He [Crowley] himself at last threw over a … plank… and jumped on it; soon afterward, swam to a bale of cotton, which floated near him.

Once merchant ship captain Chester Hilliard decided to leave the flaming Lexington, he teamed up with fireman Benjamin Cox to execute his escape plan of using a cotton bale as a raft. He testified at the inquest that aided by one of the firemen, I put the bale up on the rail…., we got on to the bale before we lowered it…. We placed ourselves one on each end of the bale, facing each other. With our weight on the bale it remained about one third out of the water…. I determined to get out of the way, believing that to remain there much longer it would become pretty hot quarters…. This was just 8 o’clock by my watch…. At the time we left the boat there were but few persons remaining on board.

Thirty others remained on the bow with pilot Stephen Manchester. After consuming the center of the ship, the fire died down. But Manchester became convinced near midnight that the steamboat could not stay afloat much longer and decided it was time to take his chances on the water. About two hours later, by his estimation, the hulk sank in the middle of the Sound in more than one hundred feet of water northwest of Port Jefferson.

Once he decided to go over the side, Manchester told the inquest jury, I … eased myself down upon the raft. There were two or three others on it already and my weight sank it. I held onto the rope until it came up again—and when it did, I sprang up and caught a piece of railing which was in the water, and from thence got on a bale of cotton where there was a man sitting… I saw another person standing on the piece of railing—asked me if there was room for another; I made no answer, and he jumped and knocked off the man that was with me; and I hauled him on again…. I think the man who was on the bale with me said his name was McKenny, and lived at New York; he died about 3 o’clock…. When I hauled him on the bale I encouraged him and told him to thrash his hands, which he did for a spell, but soon gave up pretty much. When he died he fell back on the bale and the first wave that came pushed him off it: my hands were then so frozen that I could not use them at all…. The last thing I recollect was seeing the sloop, and I raised my handkerchief between my fingers, hoping they would see me.

After the lifeboat with the captain was swamped and lost, Fireman Charles Smith testified at the inquest that I got over the stern with the intention of getting on to the rudder; I hung by the netting, kicked in three cabin windows, and lowered myself down and got on the rudder. I had stood there but a minute or two, when several others came on there also…. There was a boy got over the stern and I told him to drop overboard and get on a bale of cotton: he said he could not swim. I then told him to tell some of them on deck to throw over a bale of cotton. Some of them hove a bale over, which I jumped on after, and gave the boy my place. I swam to it, and got on it. I was on it until about 1:30 o’clock.

At that time I drifted back to the steamboat and got on her. There were then 10 or 12 persons hanging to different parts of the boat…. I stayed there until 3 o’clock, when she sank….

I swam to a piece of the [paddle] guard and with four others got on it, who all perished before daylight.