The Golden Age of Piracy is the generally recognized designation for the era spanning the 1650s to the 1730s, when maritime piracy was a momentous factor in the antiquities of the Caribbean, United Kingdom, Indian Ocean, North America, and West Africa.

Historical accounts of piracy frequently subdivide the Golden Age of Piracy into these three distinct periods:

1- The buccaneering period, around 1650 to 1680, characterized by Anglo-French seamen based in Jamaica and Tortuga attacking Spanish colonies and shipping in the Caribbean Sea and eastern Pacific Ocean.

2- The Pirate Round during the 1690s, associated with long-distance voyages made from the Americas in order to raid Muslim and East India Company targets in the Indian Ocean and Red Sea.

3- The post-Spanish Succession period of 1715 to 1726, when Anglo-American sailors and privateers left idle by the end of the War of the Spanish Succession turned en masse to piracy in the Caribbean Sea, Indian Ocean, North American eastern seaboard, and the West African coast

The modern-day perception of pirates as depicted in popular culture is primarily rooted in the Golden Age of Piracy. And incentives contributing to those engaged in piracy included the upsurge in quantities of valuable cargoes being shipped to Europe over long ocean voyages, reduced presence of European navies in many regions, enhanced training and experience that sailors had gained in European navies, particularly the British Royal Navy, and the corrupt and ineffective government administration in European overseas colonies. Piracy initially arose out of conflicts over trade and colonization among the rival European powers of Britain, Spain, Netherlands, Portugal, and France. Too, most pirates of the era were of Welsh, English, Dutch, Irish, and French nationality, and many came from deprived urbanized areas in search of a way to make money and gain standing. London in particular was known for high joblessness, over-crowding, and poverty which drove individuals to piracy that offered them the allure of power and quick riches.

Buccaneering period, c. 1650–1680; Most historians mark the beginning of the Golden Age of Piracy at around 1650, when the end of Wars of Religion permitted European countries to resume the development of their colonial empires resulting in immense economic expansion. Therefore, there was substantial money to be made, or stolen, because abundant cargo was moved via ship.

French buccaneers had established themselves on northern Hispaniola, an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles as early as 1625, but lived at first mostly as hunters rather than robbers; their transition to full-time piracy was gradual and motivated in part by Spanish efforts to wipe out both the buccaneers and the prey animals on which they depended. The buccaneers’ migration from Hispaniola’s mainland to the more defensible offshore island of Tortuga limited their resources and accelerated their piratical raids.

The growth of buccaneering on Tortuga was augmented by the English seizure of Jamaica from Spain in 1655 because the early English governors there freely granted Tortuga buccaneers letters of marque, a government license that authorized private individuals branded as a privateers or corsairs to attack and capture vessels of a foreign nation at war with the issuer. As well, the growth of Port Royal provided these raiders with a far more profitable and amusing setting to sell their booty. In the 1660s, the new French governor of Tortuga, Bertrand d’Ogeron, similarly provided privateering commissions both to his own colonists and to English cutthroats from Port Royal, and these circumstances brought Caribbean buccaneering to its peak.

Pirate Round, c. 1693–1700; As the 1690s began, a number of factors prompted Anglo-American pirates, some of whom had been introduced to piracy during the buccaneering period, to explore beyond the Caribbean to hunt treasure. The end of Britain’s Stuart period, from 1603 to 1714, during the dynasty of the House of Stuart that ended with the death of Queen Anne and the accession of King George the First from the German House of Hanover, had reestablished the prior animosity between Britain and France thus ending the profitable collaboration between English Jamaica and French Tortuga. Then the devastation of Port Royal by an earthquake in 1692 further reduced the Caribbean’s attraction by destroying the pirates’ chief market for fenced loot. Furthermore, much of the Spanish Main had simply been exhausted; Maracaibo alone had been sacked three times between 1667 and 1678, while Río de la Hacha had been raided five times and Tolú eight.

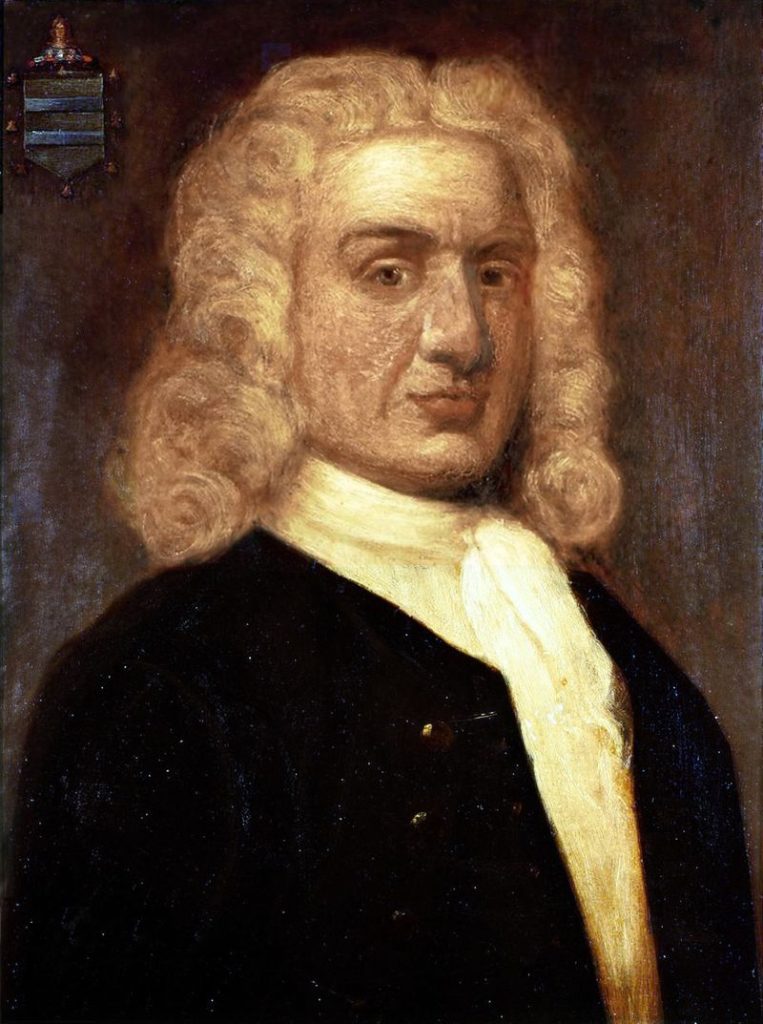

At the same time, England’s less-favored colonies, including Bermuda, New York, and Rhode Island, had become cash-starved by the Navigation Act of 1651, aimed primarily at the Dutch, that required all trade between England and the colonies to be carried in English or colonial vessels, So, merchants and governors eager for coin were willing to overlook and even underwrite pirate voyages. Although some of the pirates operating out of New England and the Middle Colonies targeted Spain’s more remote Pacific coast colonies well into the 1690s and beyond, the Indian Ocean was a richer and more tempting target. India’s economic output dwarfed Europe’s during that time, especially in high-value luxury goods such as silk and calico, which made ideal pirate booty. At the same time, no powerful navies plied the Indian Ocean, leaving both local shipping and the various East India companies’ vessels vulnerable to attack. This set the stage for the famous piracies of Thomas Tew, Henry Every, Robert Culliford, and William “Captain” Kidd.

Post–Spanish Succession period, c. 1715–1726; In 1713 and 1714, a series of peace treaties ended the War of the Spanish Succession involving many of the leading European powers that was triggered by the death in November 1700 of the childless Charles II of Spain. As a result, thousands of seamen, including European privateers who had operated in the West Indies, were relieved of military duty, at a time when cross-Atlantic colonial shipping trade was beginning to boom. In addition, European sailors who had been pushed by job loss to work onboard merchantmen including slave ships were often keen to abandon that profession and turn to pirating, providing pirate captains with a steady pool of recruits in various coasts across the Atlantic.

In 1715, pirates launched a major raid on Spanish divers working to recover gold from the sunken treasure galleon Urca de Lima near Florida. The nucleus of the pirate force was a group of former English privateers, all of whom would become enshrined in infamy; Henry Jennings, Charles Vane, Samuel Bellamy, Benjamin Hornigold, and Edward England. But although the attack was successful, contrary to their expectations, the governor of Jamaica refused to allow Jennings and his cohorts to spend their loot on his island. So with Kingston and the declining Port Royal closed to them, Hornigold, Jennings, and their comrades based themselves at Nassau, on the island of New Providence in the Bahamas. Nassau would be home for these pirates and their many recruits until the arrival of Governor Woodes Rogers in 1718, which signaled the end of their “Republic of Pirates.” Rogers and other British governors had the authority to pardon pirates under the King’s Act of Grace and while Hornigold accepted this pardon and became a privateer, others such as Blackbeard returned to piracy afterwards.

Transatlantic shipping traffic between Africa, the Caribbean, and Europe began to soar in the 18th century, a model known as the “triangular trade”, and became a rich target for piracy. Trade ships sailed from Europe to the African coast trading manufactured goods and weapons for slaves. The traders then sailed to the Caribbean to sell the slaves and return to Europe with goods such as sugar, tobacco, and cocoa. In another triangular trade route, ships carried raw materials, preserved cod, and rum to Europe, where a portion of the cargo was sold for manufactured goods, which, along with the remainder of the original load, were then transported to the Caribbean where they were exchanged for sugar and molasses, which, with some manufactured articles, were then borne to New England. Ships in the Triangular Trade often generated revenue from each port stop.

As part of the settlement of the War of the Spanish Succession, the British South Sea Company obtained the Asiento, a Spanish government contract to supply slaves to Spain’s New World colonies, which provided British traders and smugglers more access to formerly closed Spanish markets in America. This arrangement also contributed heavily to the spread of piracy across the western Atlantic. Shipping to the colonies boomed along with the flood of skilled mariners after the war. Merchant shippers used the surplus of labor to drive wages down, cut corners to maximize profits and create deplorable conditions aboard their vessels. Merchant sailors suffered from mortality rates as high or higher than the slaves being transported, and living conditions were so poor that many sailors began to prefer a freer existence as pirates.

During this time, many of the pirates had originally been either sailors for the Royal Navy, privateers, or merchant seamen. Most pirates had experienced living at sea before and so knew how harsh the conditions could be. Sailors for the king would often have very little to eat while out at sea, and would become ill and starving, or dying and that resulted in some sailors deserting the king’s service for piracy instead. Unlike other seamen, pirates had strict rules for how they were to be treated on the ships. Contrary to popular belief, pirate captains did not have dictatorship over the crews on their ships, they had to be voted in, and there were strict rules for them to follow as well. Furthermore, the captain was not treated any better, have a larger food ration, or enjoy better living conditions than the other members of the crew. And he was expected to treat the crew with respect. This was in deliberate contrast to merchant captains, who often treated their crews horribly. Most pirates had formerly served on merchant ships so knew how horrid conditions could be under some captains. Consequently, pirate ships often implemented governing councils composed of all the crew members and some councils were held daily to make everyday decisions, while others were used as a court system only when criminal incidents or legal matters necessitated it. Whatever the case, crewmembers on pirate vessels often had as much power as the captain except when in battle where the captain had full authority. And he could be removed from his position if he showed cowardice in the face of the enemy.