Each month, an interesting aspect of the world’s oldest continuous maritime service will be highlighted. The men and women of the United States Coast Guard follow in the fine tradition of the brave mariners who have served before them. As sentinels and saviors of the seas, the United States Coast Guard proudly continues its commitment to honor, respect & devotion to duty to maintain their vigil – Semper Paratus.

The Moan of the Augustus Hunt

The gale-force winds whipped across his face as if he was being slapped by Mother Nature. Lifesaver Levi Crapser pulled his oilskin cap lower on his head to try and shield himself from the onslaught of the frigid winter’s night. Walking alone along the barren beachhead he trudged onward through the monotonous duty keeping his eyes and ears open for any sign of distress. As his legs tired on his patrol along the strand, he suddenly heard an ominous and foreboding moan in the distance. The wind’s shriek had bowed to a new overture – the shrill report of a ship’s fog-horn. The lifesaver peered out toward the fog-shrouded sea. The shrill report of the foghorn again sounded. He continued on his patrol, following the melancholy moan as he searched to find the source of the signal. Suddenly, the heavy blanket of fog parted. Crapser stared out and saw the darkened hull and skeleton-like rigging of a schooner roughly a mile from the shore. As quickly as the stricken ship had shown her position, the fog returned and blanketed his view. He noted the position and as Crapser began to turn back to call upon his fellow lifesavers at his station, he saw a fellow lifesaver, Herman Bishop, who had also heard the foghorn signals. The two lifesavers briefly spoke and both men hurried across the hard-packed sands to their respective stations. Shortly after the lifesavers had parted ways, the door of the Quogue Life-Saving Station swung open amidst the gale-force winds. “There is a schooner on the bar,” Crapser bellowed as he raced into the station house. Taking a quick breath from his run, he continued, “about a mile and a half west of the station.”[1] Captain Herman quickly gathered his crew of lifesavers. Within minutes, lifesavers from the neighboring stations at Westhampton and Tiana were also on their way to the frozen strands to attempt to affect the rescue of the men aboard the unknown vessel.

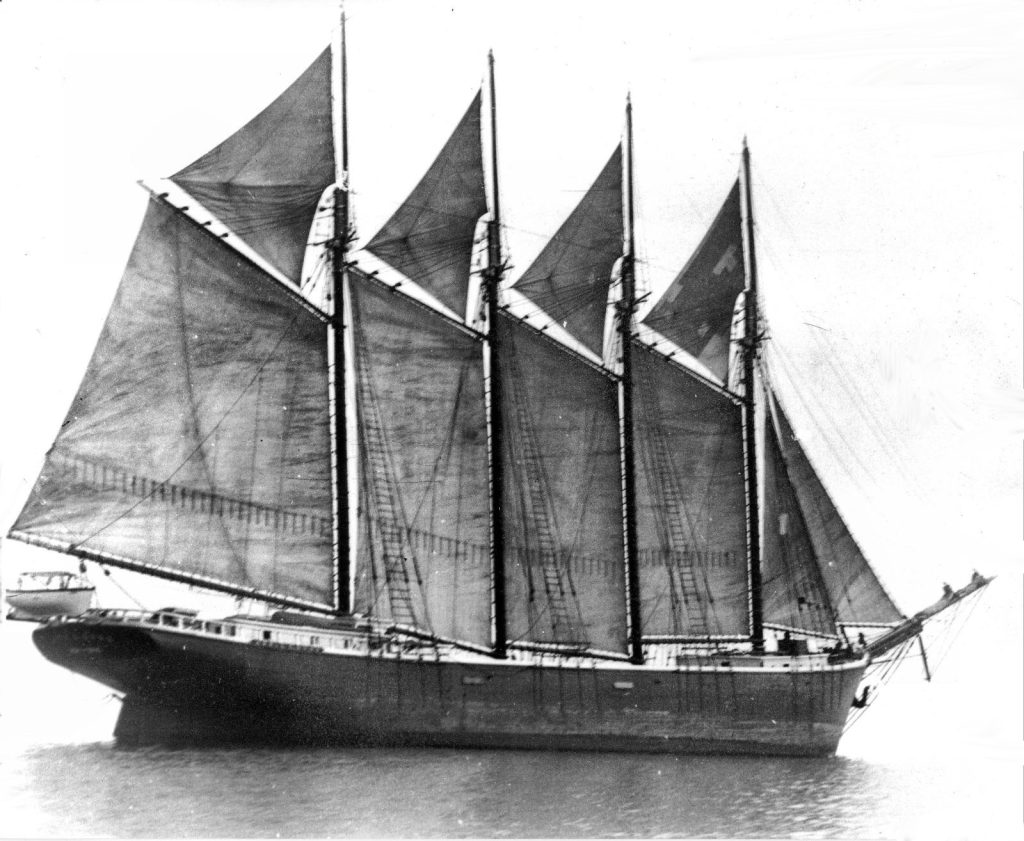

Hours earlier, around eleven-thirty on the night of January 22, 1904, First Mate William H. Conary, temporarily serving as the schooner’s master, received word from the second mate that a light had been spotted off the bow. Conary and the second mate conferred. As Conary plotted the course on his charts, the men agreed that it must be the masthead light of another ship. Based on dead reckoning navigation, Conary was confident that the Augustus Hunt was in good water, nearly twenty to twenty-five miles off of the southern shore of Long Island, New York. Captain Conary and the rest of his crew were terribly mistaken. The southwest gale had turned the Atlantic Ocean into a swirling cauldron of ice floes and surging swells. Conary and his men had furled several of the schooner’s sails earlier in the evening but as the hour neared midnight, the foresail, mainsail and four head sails remained full with the gale’s force. The schooner was plunging ahead at full speed. Suddenly, the bow of the Augustus Hunt slammed into a sandbar. The schooner shifted under the surf and was quickly beam to the seas. Frigid water poured across the decks as floes of ice slammed against the schooner’s wooden hull. Aground and with the seas on her beam, the schooner would have to wait for seas and conditions to abate to be towed. Conary ordered the foghorn signal energized and sounded. As Conary and his men attempted to save their charge, it was clear that their survival was the only option. Hopefully, the schooner would hold fast through the torrent. The men quickly retreated to the schooner’s masts to avoid the freezing waters that continued her merciless lashing at the Augustus Hunt. The melodic and piercing shrill of the foghorn sounded. The men aboard prayed that the call would provide salvation.

Captain Herman and his six men stood at the water’s edge roughly an hour after Crapser’s discovery. Additional lifesavers from the neighboring two stations arrived moments later. Despite the crashing surf and foggy conditions, Captain Herman and his men readied their Lyle guns. Shot after shot were sent in the direction of the schooner but none reached their target. The lifesavers were effectively shooting blind through the fog hoping to land a line to the men aboard. They fired not at the silhouette of the schooner but rather at the source of the screams. None of the lines bore the fruits of their labor. Meanwhile, aboard the Augustus Hunt, the men had lashed themselves to the masts of the schooner. Captain Conary, one of the mates, and the cook had sought refuge in the after masts. Two of the crew chose the fore-rigging and John Miller, George Eberts, the second mate, and Carl Sommers, a sailor, were lashed to the foremast. The huge waves showered icy water on the men as they clung to the masts and rigging. The men called out for help and it was as if their calls were going unanswered. Suddenly the after mast was torn from the schooner and disappeared into the black swirling cauldron. The voices of the captain, one of the mates and the cook went silent in an instant.

Efforts to reach the stricken schooner with the line throwing guns were adversely affected by the severe weather; however, the lifesavers realized that despite the horrendous surf conditions, the lifeboat would have to be launched. Frustratingly, the lifeboat was as ineffectual as the initial actions of the Lyle line throwing guns. As the hours passed and the hour of dawn approached, the foghorn’s shrill report silenced. The sound that replaced its call was even more heartbreaking. It was the moans and screams of the men lashed to the masts of the Augustus Hunt. The lifesavers turned their jacket collars upward and pulled their oilskin covers lower to try to stave off the cold and to in effect, muffle the melancholy and maddening murmurs from the men aboard the schooner. Not being able to help was painful. Meanwhile, in the foremast of the Augustus Hunt, John Miller yelled to Eberts and Sommers. He had reached his physical limit of pain. He wished them both well and unleashed himself from the mast. Miller was swept from the mast in the next wave and the men never saw him again. The schooner continued to break apart amidst the maelstrom.

At approximately nine o’clock in the morning, with a backdrop of roughly a hundred locals, the lifesavers heard a dreadful death rattle emanate from the sand bar. The near constant onslaught of ice flow filled swells had savagely torn through the wooden hull of the schooner. The decks buckled and splintered. The masts shattered apart and tumbled into the sea. Through the din, the lifesavers began to spot the flotsam of the carnage. The moans and shouts from the schooner had abated into a soft and haunting murmur of last words. A box was pulled from the shallows. It contained documents from the captain’s quarters. The ship had broken up and now the stricken schooner had a name. The lifesavers once again launched the lifeboat into the surging swells, steadfastly determined to affect a rescue. Despite their efforts, the lifeboat was capsized no more than twenty feet from shore. The breakers were too steep, powerful, and peppered with broken pieces of the ship and her cargo. Suddenly, a cry from one of the lifesavers was heard. He pointed through the fog to a fortunate sight. Two specks, appearing to be men, appeared lashed to a piece of one of the schooner’s booms. The lifesavers grabbed their Lyle guns and a volley was fired toward the men. The lines were rebuffed by the winds but the lines were now within reach. Hauled in and reset, the second round of lines pierced through the winds. One line reached one of the stricken men on the wrecked mast. Despite his near frozen hands, the unknown man tied the line off to the stump of the mast. The lifesavers pulled on the line but to no avail.

Realizing that their efforts to pull in the debris were in vain, the lifesavers shifted their approach and formed a Hillman Line out into the surging surf. In effect a tethered human chain, the technique was to provide an extended reach in difficult surf conditions. As the lifesavers continued to extend into the maelstrom and to bring the men to safety, they saw one of the men leap into the water. Surfman William Halsey saw Eberts leap into the frigid waters and took immediate action. Tied off with a line and with a lifejacket under one arm, Halsey dove into the water and began swimming toward the nearly frozen mate. Pulling him to shallower waters, Halsey placed him in the lifejacket and pulled him toward the strand. Sommers followed suit and dove into the water. Surfman Frank D. Warner swam through the debris and grabbed a hold of his shirt. Returning to the beachhead, the lifesavers had successfully pulled two of the crew of the Augustus Hunt to safety.

Captain Robert Blair arrived in Quogue, Long Island on January 24th. As he took off his cap and held it in his hands, he nodded in affirmation to the coroner on the corpse’s identification. The body that had washed ashore was his first mate, William Conary. He also sadly identified another body, that of the schooner’s machinist, Charles Hudson. Both of the bodies bore the savagery of their last hours on earth – both were severely battered, bruised and torn apart by the conditions and debris-littered waters. Blair had been sick in Boston and Conary had been tasked with the Norfolk, Virginia to Boston, Massachusetts voyage. It had been Captain Conary’s first voyage as the schooner’s captain. After leaving the coroner’s office, Captain Blair met with Second Mate George Ebert and the only other survivor, Carl Sommers. While Ebert was fully cognizant and in recovery, Sommers was less aware. He stammered softly about the wreck but he was found confusing the wreck of the Augustus Hunt with the wreck of the Joseph J. Pharo – a wreck he and some of those from the Augustus Hunt had survived only weeks prior. Captain Blair, after spending time with his remaining crew, visited the site of the tragedy. The sea had calmed and it was now time to try and determine if anything of the Augustus Hunt could be salvaged. As Captain Blair walked along the debris strewn sands, the hulk of his schooner lay in ruins offshore. The voices of eight of his men had been silenced. As Captain Blair contemplated the horrific end of his shipmates and his vessel, the lifesavers remained on patrol along the strands for the bodies that had not yet been released by the sea.

In the wake of the loss of the Augustus Hunt, the lifesavers continued on their patrols along the strands, Costen light in hand, amid the peaceful and the rough, to ensure that if there were mariners in distress, they could raise the alarm and render aid. Surfmen W.F. Halsey and Frank Warner would eventually receive the United States Life-Saving Service’s Gold Medal for their heroic efforts in saving the two men of the Augustus Hunt. The wreck and rescue of the Augustus Hunt by the hearty band of lifesavers exemplified the dedication to others that remain a cornerstone of the efforts and missions of the men and women of the United States Coast Guard. Guided through the fogginess of uncertainty, the guardians will continue to forge through the din and render aid, not unlike the lifesavers on that frigid and foggy night in January of 1904, as true examples of the sentinels and saviors of the seas.