Ice shrouded the rigging and angry seas swept over the deck as the Resolute plunged through the North Atlantic. Sailing out of New London, Connecticut on the whaler George Henry, Captain James Buddington found the British ship HMS Resolute locked in the ice, abandoned. The Resolute had been sent by the British government to find the missing Franklin Expedition which had been searching for the fabled Northwest Passage.

By the middle of the 19th century much of the world had been explored except for the Arctic regions. The public, particularly the British, were fascinated by arctic exploration. The three primary objectives for explorers were to reach the North and South Poles and to find the mythical Northwest Passage. The Northwest Passage was thought to be a shorter trade route from Europe to Asia. The belief that a route lay to the far north persisted for several centuries and led to numerous expeditions into the Arctic.

In 1845 the Franklin Expedition, consisting of two ships, set sail from England with a crew of 24 officers and 104 men under the command of Rear-Admiral Sir John Franklin to search for the Passage. Two years went by with no word from the expedition. Public concern began to grow. Lady Jane Franklin, as well as members of Parliament and British newspapers, urged the Admiralty to send a search party. Three expeditions were launched but they found no sign of the missing ships. By 1850 five years had passed without any word the desperate Admiralty offered a £20,000 reward.

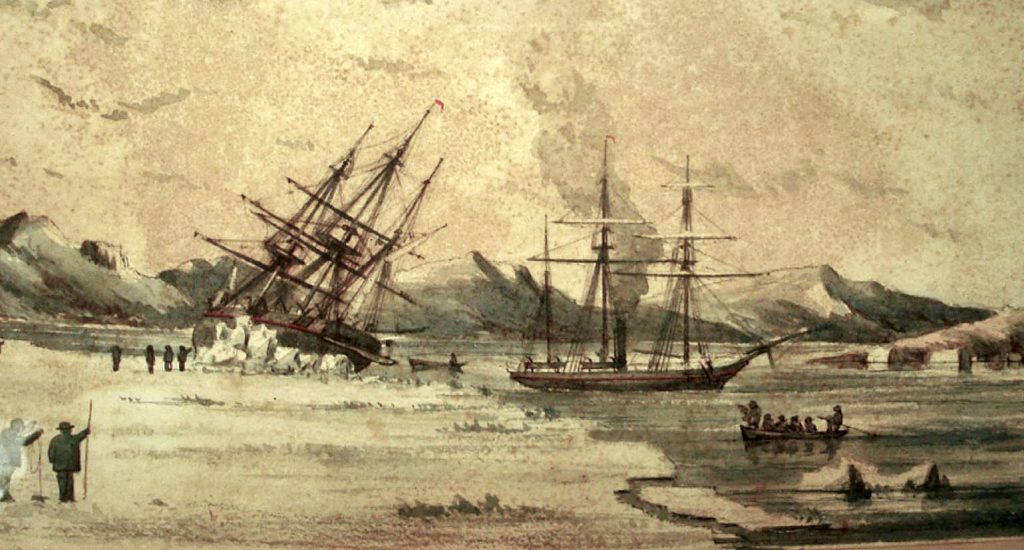

In 1852 the British government mounted a major effort to determine Franklin’s fate. Command of the expedition was given to Sir Edward Belcher, a political appointee, who had never served in the Arctic. He was not experienced in commanding vessels in the ice. Five ships set out and became frozen in. After enduring two polar winters with four of his five ships trapped in ice Belcher abandoned the ships against the advice of his officers. He and the crews returned to England. Belcher was court-martialed but later acquitted. No one thought any of the ships would ever be seen again, but the Resolute was a specially constructed 600 ton ship. She was iron strapped for work in the ice and she survived.

The Resolute had drifted for sixteen months with the ice pack, traveling through Baffin Bay to Davis Straight, a distance of over 1100 miles. It was here that Captain Buddington sighted the abandoned vessel. Buddington had carefully sailed the George Henry along the edge of the ice looking for whales when an opening appeared. Climbing up to the crows-nest he was surprised to see a ship in the distance. The ship was listing badly and the masts were bare. Buddington could see that she was held fast by ice and looked to be abandoned.

Bringing his ship as close as possible to the Resolute he sent his first and second mates with two crewmen over to investigate. With difficulty the party crossed the rough ice and reached the abandoned vessel. The crew climbed aboard and entered the main cabin. They were amazed that the cabin appeared as if the captain had just stepped out. Returning, they reported that the ship was the Resolute. Except for seven feet of water in the hold and ice thickly encrusted on the port side, the ship was well provisioned and surprisingly had no major damage.

Buddington decided it might be more profitable to rescue the Resolute and sell the vessel for salvage than continue with an unsuccessful whale hunt. He came up with a daring plan to rescue the ship. Half his crew would sail the George Henry back to New London. The other half, only 13 men, would sail the Resolute, a ship that was usually crewed by 80, to New London.

The difficult voyage began on October 21, 1855. Buddington’s biggest problem was the lack of navigational instruments; he had only his watch, a quadrant and an old compass. His only chart was a rough sketch of the coast but he had his lifetime of seafaring experience to fall back on. Heading south, the Resolute and her small crew sailed through one storm after another, finally being blown far to the south by a hurricane. They were cold and worn out by the unrelenting work of driving the big ship. New London and home seemed a long way away.

Buddington wrote about the voyage, “After a stormy passage of 64 days having in that time a succession of gales, and being driven as far south as Bermuda, we at last reached the port of New London, and came to anchor Sunday, December 23, 1855.”

Buddington brought the Resolute into New London during one of the coldest winters ever recorded in New England. Long Island Sound and the Thames River were both frozen over. New London was the second largest whaling port in the world and everyone in town was somehow connected to whaling. So when word got out about Captain Buddington’s incredible voyage and the ghost ship he had rescued thousands of spectators lined the shore to see the famous ship in spite of the cold. Because of the crowds the ship was anchored out, even so, souvenir hunters managed to steal parts of the ship. Many of these artifacts can be viewed today at the New London County Historical Society Museum.

The owners of the George Henry were eventually awarded the salvage rights. At the time of the salvage in 1855, Britain and America had several areas of active dispute. A bill was proposed in Congress for the federal government to purchase the Resolute for $40,000, refurbish her, and give her as a present to the Britain’ to help ease tensions between the two countries. The vessel was refitted and sailed to England. She was presented as a gift to Queen Victoria and accepted as a token of American friendship.

After her return to England the Resolute served in the Royal Navy another 23 years until being retired in 1879. She was finally broken up and her wood salvaged. Queen Victoria ordered four elaborate writing desks built from her white oak timbers. The first desk was known as the Resolute desk and was presented to U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880. Since then it has been used by seven American Presidents as their official desk in the Oval Office. A smaller lady’s desk, known as the Queen Victoria desk, was presented to the widow of Henry Grinnell in 1880 in recognition of her husband’s contributions to the search for the lost Franklin Expedition. In 1983 it was given to the New Bedford Whaling Museum and is in their collection today. Queen Victoria had two smaller desks made for herself and they remain part of the Royal Collection.

The mystery of what happened to Franklin and the 128 men of the lost expedition was finally solved in 1857, eleven years after their disappearance, when the remnants of the once great Franklin Expedition were found on a barren Arctic shore. The only written record of the expedition’s struggles, along with skeletons and other evidence, told a grim tale of scurvy and starvation.

Captain Buddington retired to his home at Poquonnock Bridge in Groton, Connecticut after 50 years at sea aboard 17 different vessels. He died December 23, 1908 at the age of 91, exactly 53 years to the day after he brought the Resolute into New London Harbor. The hero of the Resolute saga claimed that he never received any payment from the owners of the George Henry for his part in the salvage. In court, they claimed that Captain Buddington had broken his contract by abandoning his command of the George Henry and a judge agreed.

There is no doubt that the salvage and subsequent voyage of the Resolute under the command of Captain Buddington is one of the greatest seafaring feats in the age of sail. It truly was an age of wooden ships and iron men.