We’re onboard a modern warship in the Persian Gulf:

“There is nothing on this chart that says what sort of holding ground we have, Senior Chief.”

“Oyster beds, Captain. Ten fathoms and oyster shells.”

The captain looked up. “You’ve anchored here before, Senior?”

“No sir. Never been this high up in the Gulf before.”

The captain raised an eyebrow. “Oysters in the Persian Gulf? I doubt it.”

“Oysters, Captain, you can bet the ranch on it.”

“How are you so sure, Senior?”

The senior Chief reached down and lifted up a heavy grey book, put it on the wardroom table, and opened it to a marked page. Then he turned it around for his captain to read.

“Oysters, Captain.”

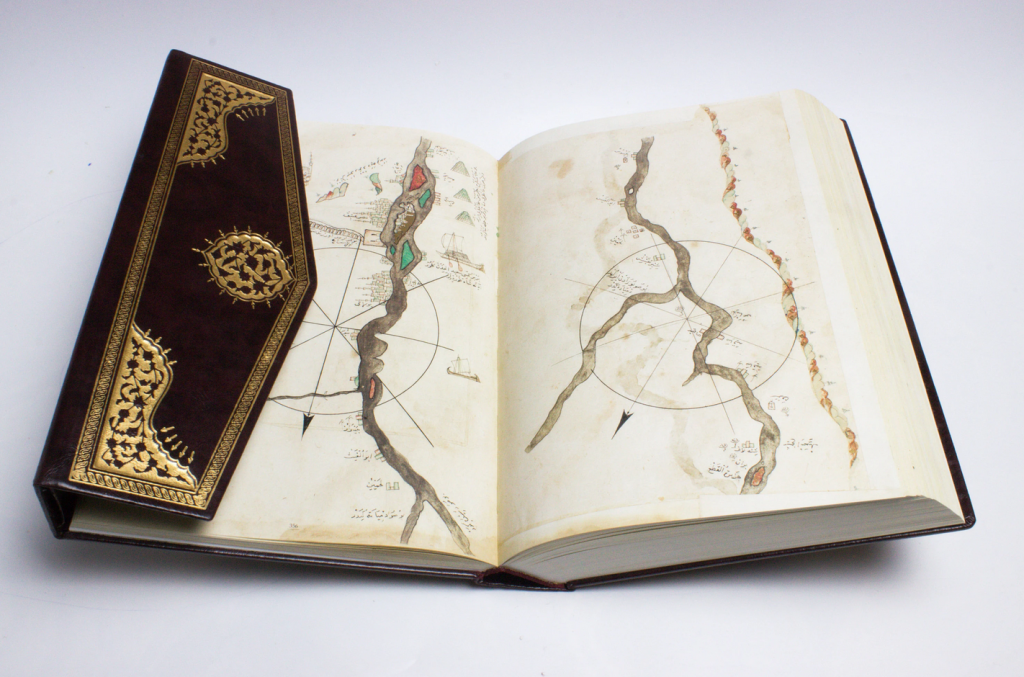

The book was a copy of the Kitab-i Bahriye by Piri Reis, newly translated into English by the government of Turkey.

American and European navigators know the name Piri Reis, but have little understanding of just who he was, when he lived, his record in the Turkish Navy, or how his writing impacts navigation today.

Piri Reis was born in a province of Turkey between 1465 and 1470. By the time he was fifteen he had become a privateer or Corsair. The first mention of Piri Reis in official records occurs in 1499 when he commanded a ship in a war between Venice and Turkey. In 1516 he was part of an expedition against Egypt in which the Turks captured the port city of Alexandria. Later he became the admiral of all forces in the Persian Gulf and engaged in several battles against the Portuguese who were then moving into the Indian Ocean. Finally, court intrigues and the ravages of the Portuguese caught up with him. In 1554 Piri Reis was executed.

His military record was impressive, but his record as the foremost navigator of his time is more so. When not on military campaigns, Piri Reis worked writing his book, the Kitab-i Bahriye (which translates to mean The Book of the Sea), a comprehensive volume of all navigational knowledge, maritime history and folklore of the time. Given his Turkish perspective, it is understandable that most of his work went into detailed descriptions of the Mediterranean, cataloguing every island, port, anchorage and channel from Istanbul to Gibraltar.

In this one book the Turkish navigator created a single source work defining the geography of the known world. When coupled with his charts, his navigational work towers above his contemporaries. Bahiye was completed in 1525, more than 30 years after the “discovery” of the new world by Christopher Columbus. Interestingly, Piri Reis does not credit Columbus with that discovery. His work is quite explicit. The Portuguese not only discovered the coast of South America, but were actively using it as early as 1465.

In the Bahriye, Reis combined his own experiences and observations, added the knowledge of others and produced a composite work. His descriptions made over 500 years ago are accurate today and attest to the accuracy of information he received. By comparing his observations to what is known today, it is possible to make reliable estimations in other areas as well. If his work is as accurate in its history as it is accurate in its geography, then Portugal, not Spain, discovered the new world.

The works of Piri Reis were unavailable to the general public until the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Turkish Republic published the Kitab-i Bahriye in 1988. That translation contains photos of the original text on the left, and a simultaneous translation into modern Turkish and English on the right. The text is divided into four volumes, the first of which is ISBN number 975-17-0280-X. The first translations of Bahriye were made in 1756 but were never published. In the years following, the whole text, or just parts of it, were copied by hand and sent to Germany and France. Of the original work, only 29 copies are known to still exist and each of these are hand-written manuscripts. All but nine of these remain in Turkey.

Piri Reis held a dim view of Kolon (Christopher Columbus). The Moors were kicked out of Spain in 1492. Piri Reis, a Turk and a Muslim, thought equally little of the Spanish. He gives Kolon short shift in the history of the discovery of the new world.

He wrote:

Hear also how that land (Antilye) was discovered. Let me explain so that is will be clear. In Genoa there was a star gazer whose name was Kolon. A curious book came to his possession that without doubt was from the time of Iskender (Alexander the Great, a generic term Reis uses for Egypt). In the book they had collected and written down all that was known about navigation. That book ultimately reached the land of the Franks (generic name for Europe), but they knew not what was in it. Kolon found this book and read it, whereupon he took it to the king of Spain. And when he told the king of all that was written therein, the king gave him ships. Goodfriend, employing that book, Kolon sailed and reached Antilye. After that he ceased not but explored those lands Thus the route has become known to all. His map too has reached us. That is the situation and I have told it all to you.

Reis refers to Columbus as “that star gazer from Genoa .” For the Portuguese, Reis held much greater respect. Here the Bahriye creates far more questions than it answers, at least to Western history.

When it became clear that Egypt would be conquered, the leaders of that country fled. They fled to the land of the Franks, crossing over the sea to the other side. And that book remaining from the time of Iskender that I mentioned, they took with them as they fled. They came and conquered many lands. They have that book translated from one end to the other in their own language. If you would know the truth of the matter, let me tell you who did the translation too. It was a man they called Bortolomye (probably Bartholomew Dias, 1450-1500). He is the one they say did the translation.

On another page (page 189, vol. 1), Reis states that the Antillies were discovered on the eight hurdredth and seventh year of Hegira, or 1465. He makes quite a point of saying the Anrtillies were not just a bunch of islands. The key that makes the date 1465 stand out – and that Reis believed that the Portuguese were the actual discoverers of the new world – is contained in his description of how the Portuguese got to India. The Portuguese did not sail down the coast of Africa. Along the west coast of Africa are barrier reefs, and few places to find fresh water. They went in another direction entirely.

If one is to go from Portugal to India, this can only be done by starting in the spring. As is the case in the religion of the unbelievers, they make their preparations and set out in three days. After setting out from Portugal they proceed west-southwest for seven hundred miles or so. After completing the seven hundred miles they reach a place called Maderia. This Maderia is known as an island and one finds sugar cane here with large spikes. After taking on water at this island, they proceed on their voyage southwards. After passing one thousand two hundred miles beyond Maderia they reach Kavu Verde (Cape Verde). The Portuguese travel thence to India, listen to my words. How do they go there?

Opposite that cape there are islands numbering eight or so. From this cape to these islands is four hundred miles to the west. Thus they arrive there and rest. Taking on water they proceed on their voyage. From here they advance two thousand or so miles southwest, where they will find themselves facing a shore at their destination. This place is called the continent of Birzillu, the meaning of which is “plenty of dye.” For there is plenty of dye there, but the voyage is difficult and long. After seeing these places they again set out onto the vast sea. Know that they proceed going fully southwest. Now they sail south-southwest and this time they use the astrolabe. They proceed on this voyage using the astrolabe until they reach the fifty-fifth parallel.

What the Portuguese did then, was to sail west to Brazil, down the coast of South America, and then back across the Atlantic. This allowed them to get the fresh water they needed for the cruise, fresh water being difficult to get on the coast of Africa.

It is apparent reading the Bahriye that the Portuguese knew about the existence of lands to the west long before Kolon ever guessed they were there. It is also apparent the Portuguese were visiting the coast of South America regularly long before Kolon ever left Cadiz.

All of this is important to the professional mariner and the maritime historian. Reis raises many questions begging for answers. Did there exist an Egyptian text that described lands to the west of Portugal? If so, how did the Egyptians know about them? Did the Portuguese know about that text and start their trips to America earlier than Columbus? Reis says that they did , but more is needed than the Bahriye to confirm this assertion. Perhaps somewhere in the archives of Portugal, there exists an Egyptian text that will throw all the ideas of Western history about the discovery of the new world out the window.

The Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Turkish Republic has done an invaluable service to mariners throughout the world by publishing this book with an English translation. The problem with the Bahriye is finding a copy. We tend to think of navigation as a Western art form. Europeans invented the sextant, the chronometer, discovered the new world and so on. We tend to overlook entirely the invaluable contributions to navigation the Turkish and Arab navigators of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries By overlooking these contributions we have missed so much of what is valuable even today.

Back onboard our modern warship in the Persian Gulf:

The anchor, when raised in ten fathoms of water in the northern Persian Gulf, was covered with oyster shells. Piri Reis was right in 1525 and remains so nearly 500 years later.