On the night of February 11, 1907, only two miles off Watch Hill, the wooden paddlewheel steamship Larchmont, on the New York/Providence run, and the lumber schooner, the Harry P. Knowlton collided. As many as 150 people perished that night. The exact figure is not known but it was the worst maritime disaster in Rhode Island’s history.

Imagine what that night of terror must have been like. The Larchmont’s main salon was filled with the sound of happy people, white tablecloths, fine china, and silverware glisten in the light from crystal chandeliers. Retiring to your cabin you can hear the wind roaring outside on deck. How cozy your cabin feels. Suddenly the cabin vibrates violently, you hear a deep roaring sound and the cabin goes dark. You fumble in the dark for your spectacles and bathrobe. You smell something burning, pushing down panic you stumble out into the passageway filled with other passengers. No one knows what’s happening. Shouts and screams fill your ears as the passageway fills with smoke and the ship starts to list. Struggling to get to the exit you emerge into the stormy night. The cold shocks you, in only seconds you’re freezing from the icy spray driven by a 50-mile per hour wind. The air temperature is 3 degrees below zero and the wind chill is 30 below. You suddenly realize that you’re probably not going to make it. The cost of your passage to New York that day was one dollar. That night, one dollar bought you a one-way ticket to hell.

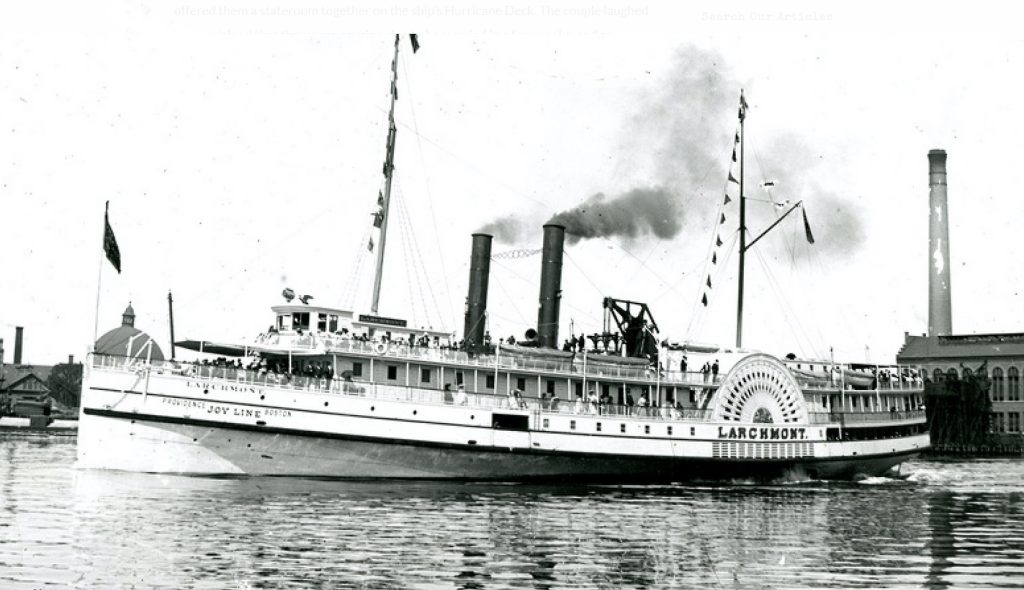

The Knowlton had been icebound in the Hudson River so when the ice freed her, she put up all sails to make up for lost time. About 10:45 that stormy night she struck the Larchmont. The Larchmont was a large ship, 252 feet long with a beam of 37 feet and drew 14 feet of water. She had a gross tonnage of 1606 tons. The Harry Knowlton displaced 317 tons and was 128 feet long, about half the length of the Larchmont, and carried a cargo of 400 tons of coal.

Some people have said the Larchmont was a cursed ship. Originally, she was named the Cumberland. There’s an old saying that it is bad luck to change the name of a ship and this certainly seemed to be true in her case. Built for the International Steamship Company in 1885 she ran between Boston and Nova Scotia for many years without incident. In 1902 she was sold to the Joy Line and renamed the Larchmont.

The newly named Larchmont had a run of bad luck from the very first. On October 4, 1902, five days after her maiden voyage, a pile of mattresses caught fire but the fire was quickly brought under control. On January 24, 1904 she ran aground off Prudence Island near Bristol, Rhode Island. This performance was repeated off Warwick Light in Narragansett Bay inside of two weeks. Eight months later, on October 11, she collided with the lumber schooner DJ Mountson off Stamford, Connecticut. Then, on February 19, 1905 twenty-five year old John Harta, a Providence engineer, was shot in the head and robbed while asleep in his cabin. His murderer was never caught. A fire broke out again on January 11, 1906. Caused by a defective electrical connection the fire was quickly brought under control.

On her last voyage to New York, the Larchmont was under the command of 27-year-old Captain George W. McVay. He was the youngest captain in the fleet and his first command. The Larchmont left Providence, steamed down the East Passage, and by 9:30 that night was off Point Judith, Rhode Island. The wind which had been picking up since she left Providence increased to a violent 50-mile per hour gale. As the Larchmont proceeded into Block Island Sound salt spray from towering waves lashed at the ship. Everything on deck was covered with a fine layer of ice. In the salon, people gathered to chat, drink, and eat. Captain McVay, having finished his rounds, returned to the wheelhouse. He commented briefly on the foul weather to Larchmont’s first pilot John Anson, then leaving Anson in command Captain McVay went to his cabin. He began to sign some papers when Anson suddenly yanked the Larchmont’s whistle cord four blasts. For a split second McVay was uncomprehending and then he realized it was the danger signal.

Out of the darkness Anson had seen the lights of the Harry Knowlton. She was commanded by Captain Frank P. Haley, a 60-year-old hardened veteran of 46 years in the coasters. Aboard the Knowlton the mate at the wheel yelled to Captain Haley who was below in his cabin, he immediately came on deck. Not more than 400 yards away the portlight of the Larchmont was visible and the two ships were heading directly for each other. The mate turned to the skipper and yelled into the teeth of the storm, “He ain’t going to clear us, Captain.” Haley didn’t reply. The Knowlton, under sail, had the right of way. “Keep on course”, Haley ordered and swore under his breath, “those steamers”. “Aye, aye, Sir” responded the mate as he gripped the wheel even tighter.

On the Larchmont, Anson must have realized the ship was in imminent danger. He had just released the whistle when he yelled at the helmsman, “For God’s sake, Staples, port the wheel! Port the wheel!” Quartermaster Staples shoved the wheel over as far as she would go and hung on and prayed. Anson’s command, whether done out of fright or ignorance or both, was the worst possible one he could have given. It drove the Larchmont to starboard, directly into the path of the on-rushing Knowlton. By then McVay had reached the pilothouse but it was too late. “My God, John Anson”, he groaned, “What have you done?”

The two ships struck with tremendous force. The sharp bow of the Knowlton cut deeply into the side of the Larchmont just in front of the paddlewheel. The Larchmont’s main steam line was severed leaving her without power. Hoping to save people trapped on the far side he gave the order to lower his boat. The gale-force winds quickly drove his boat away from the ship, removing any chance of rescue. The Larchmont sank in less than 10 minutes. In the subsequent hearing, Captain McVay had to defend himself against charges of cowardice for leaving the ship. He insisted that he did everything he could to save the lives of his passengers.

Aboard the Knowlton, the crew took to her lifeboat hoping to be rescued by the Larchmont. They signaled the Larchmont for assistance but the steamship had already sunk. Eventually, they made it to shore at Charlestown, Rhode Island suffering from frostbite and hypothermia.

In the early morning hours of February 12, a lifeboat from the Larchmont, containing Fred Helgessel and six dead companions, ran aground on Block Island. Young Helgessel staggered ashore. He made his way up to the North Lighthouse to summon help. Upon learning of the disaster many Block Island fishermen put to sea in search of survivors. The fishing boat Elsie spotted the wreckage of the hurricane deck. With 15 people clinging to it only 8 of them were still alive and 7 frozen to death. In all, there were only 17 survivors from the Larchmont including the captain, the purser, and the quartermaster.

The cold was so intense that night that a man in one of the Larchmont’s lifeboats went insane and slit his own throat to end his agony. For days frozen bodies from the Larchmont came ashore at Block Island. Seventy-four bodies washed up and were stacked like cordwood, loaded aboard wagons, and taken to where they were finally shipped home. For weeks newspapers carried accounts of the sinking and the subsequent trial. Both captains survived and would blame one another for the tragedy. After the investigation the pilot Anson, who went down with the ship, was blamed for steering the Larchmont in the wrong direction when approaching the schooner. The purser, Oscar Young, claimed the passenger manifest was aboard the Larchmont, therefore he did not know the exact number of passengers on board but on his deathbed, he said that there were at least 150 people on board.

The sinking of the Larchmont was one of the worst maritime disasters in US history. Many questions still remain about the cause of the wreck, was it Captain McVay’s inexperience? A raging gale was blowing that night, visibility was poor, and the ship was in congested waters. It seems a strange time for the captain of a ship to retire to his cabin leaving the pilot in charge. Or did the pilot, John Anson, panic when he gave that fateful order to the helmsman at the last minute? Captain Haley had the right of way but was his decision to carry on despite the danger the right one? The mystery of what happened that terrible night will probably forever remain unsolved.