New York’s worst maritime disaster and the nation’s second deadliest maritime didn’t happen off the coast in the Atlantic Ocean or Long Island Sound but in the East River less than a few hundred feet from shore.

On June 15, 1904, crowds of happy people, mostly women and children, stood in line to board the Passenger steamship General Slocum for their church’s annual picnic. For the last 14 years they had celebrated with an annual picnic and almost 1400 people had signed up for the event. The General Slocum, named after Civil War General Henry Warren Slocum, Sr., was 250 feet in length and the largest excursion steamship in the state of New York. Little did the people who boarded the large ship that morning know that, for most, that day would be their last?

Captain William van Schaick stood on deck greeting people. The Captain came from a seafaring family and had dreamed of one day being captain of the largest excursion steamship in New York and he had succeeded. He had successfully commanded the General Slocum for 13 years.

A band played, bells jingled, as the massive paddle wheels began to churn the water. The crowd cheered as the steamer got underway up the East River toward Long Island Sound. Only twenty minutes later the ship was passing 96 Street when a crew member walking to the galley noticed a small fire in the forward storage room. The fire was fueled by straw, oily rags, and lamp oil that were strewn around the floor. It was reported that a small boy had warned of the fire 10 minutes earlier but he wasn’t believed.

In any event the fire was not reported until the ship had reached 136th Street. One account says the crewman who discovered the fire threw down his whiskey bottle and ran to find the mate, an indication of the low quality of the crew. It could have been that seaman or another’s thrown cigarette that started the fire. It was also reported that the mate upon seeing the fire seemed confused and instead of taking immediate action reported the fire to Captain van Schaick who sounded the alarm. By this time the fire had spread.

Twenty minutes after leaving the dock a great flower of flame shot out of the vessel and instead of turning directly into the Bronx shore only 300 feet away, van Schaick, unaccountably, ordered the helmsman to head for North Brother Island, a mile ahead. This single decision by the captain cost the lives of countless souls because as the Slocum steamed at full speed into the wind, it fanned the flames at the bow. The fire quickly became a terrifying conflagration. A young boy climbed a flag pole to avoid the fire but it collapsed into the inferno and he was burned alive. The crew grabbing the one fire hose found that the old linen hose was completely rotten. Turning to the lifeboats they found they were tied up and inaccessible, some reports claim they were wired and painted in place, more evidence that the ship’s safety equipment had not been maintained at all.

Hundreds of passengers crammed into the stern trying to avoid the flamed. Screams filled the air as horror stricken passengers strapped on life vests that turned to dust. The life vests were cheaply made and instead of having the 6 pounds of cork, as required, were filled with granulated cork and an iron bar inserted for weigh. They had been left outside exposed to the weather for 13 years and were completely useless. Many of the women dressed in the heavy woolen clothing of the day immediately sank when they jumped in the water.

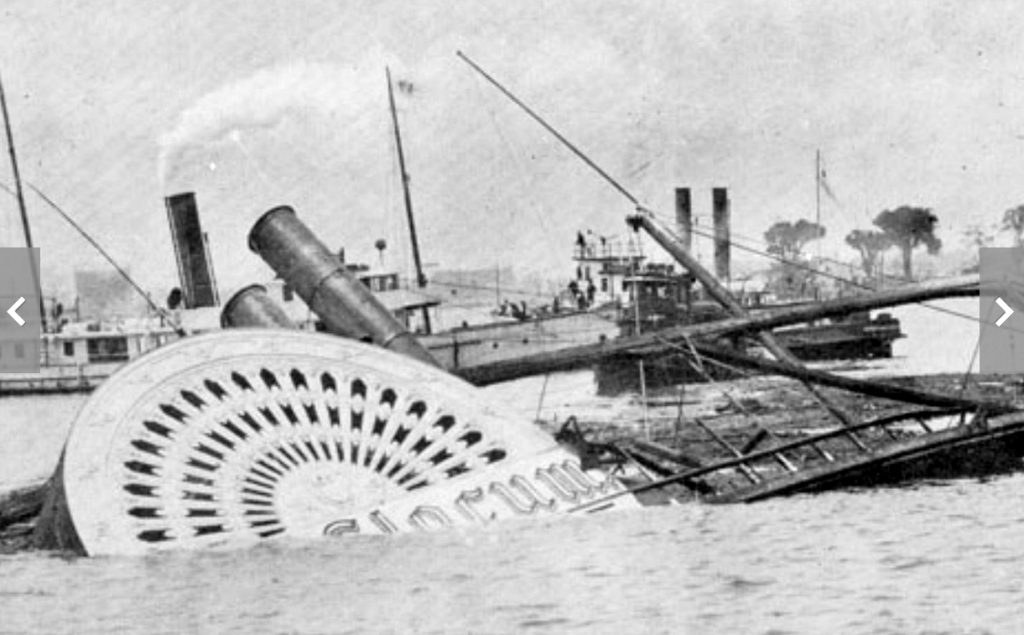

As the General Slocum slammed into the rocks of North Brother Island the impact caused the hurricane deck to give way throwing hundreds into the blazing inferno where they were instantly burned to death. The Slocum drifted free of the island and finally came to rest at Hunts Point where a tug rescued about 150 people. Captain van Schaick, the two pilots, and the entire crew, except for the chief engineer, were some of the first to leave the ship. The official death toll was put at 1,021.

As news of the disaster spread newspapers all over the country demanded justice and Captain van Schaick and the crew were arrested. Eight people were indicted by a federal grand jury after the disaster: the captain, two inspectors, and the president, secretary, treasurer, and commodore of the Knickerbocker Steamship Company, owners of the General Slocum. Company President Frank A. Barnaby claimed that it had paid for and maintained the ship in a safe condition but the evidence they presented was highly suspect and the Inquest found the officers and directors of the company guilty of manslaughter, however Captain van Schaick was the only one charged. This illustrates how reluctant courts were to prosecute corporations back then.

During his trial, Captain van Schaick, despite a record of 40 years’ service, was found guilty of criminal neglect in not having a useful fire hose, staunch lifeboats, and life-preservers that worked. Other offenses included for allowing rubbish to collect in the store rooms; for having a crew made up of unqualified and untrained personnel, and for not holding fire drills. He was sentenced to the maximum 10 years in prison.

Captain van Schaick was 72 years old when he was sentenced. During his trial he met and married a younger woman just before he left to serve his time at the notorious Sing Sing Prison. He is quoted as saying, “Today, instead of being a criminal I should be considered a hero. I hope for a pardon.” Apparently many people including many other steamboat captains agreed with him. They thought that the company should have borne the brunt of guilt for the disaster and that the captain had been used as a scapegoat. The new Mrs. Van Schaick became his tireless advocate and started a petition, signed by over 200,000 people for his release. President Theodore Roosevelt refused to grant him a pardon but on Christmas day, 1911, a new President William Howard Taft granted it.

The old captain went back to his young wife and they moved to a farm outside of Utica, New York but the couple soon separated. Captain van Schaick now a thin, rickety old man, his face haunted by the tragedy he was at least partially responsible for died December 8, 1927 at the age of 90.

Pride of the New York fleet, the once beautiful General Slocum’s burned hulk was raised from the East River and converted into a coal barge. She was renamed the Maryland and transported coal for 4 years before sinking in a storm off Sandy Hook, New Jersey on December 3, 1911. The four seamen aboard were all rescued.

It was corporate greed and one captain’s negligence that led to New York’s greatest maritime disaster of all time.