Captain Murray stepped onto the bridge and scanned the horizon. The gale-whipped waves crested as his charge, the S.S. Alaska of the Guion Line, neared the waters off Fire Island, Long Island. In the distance, he finally spotted the torch of a pilot boat approaching. Captain Murray told the watch officer to note the time in the logbook, twenty-minutes to midnight, December 2, 1883. The pilot boat was approaching from the southwest. With the logbook entry written in, Captain Murray passed a secondary order to light the blue lights. This would confirm his request for pilotage assistance. Captain Murray paced the bridge as he anxiously awaited the pilot to come alongside, lower the yawl and come aboard. The storm had grown tiresome, and his passengers were excited to reach New York. The weather and sea conditions were less than ideal, but for the pilots and crew aboard the pilot boat Columbia No. 8, this was just another day performing their important duties for the safety of the passengers and vessels that entered New York Harbor. Little did they know that the safety of their own lives was about to be placed into jeopardy.

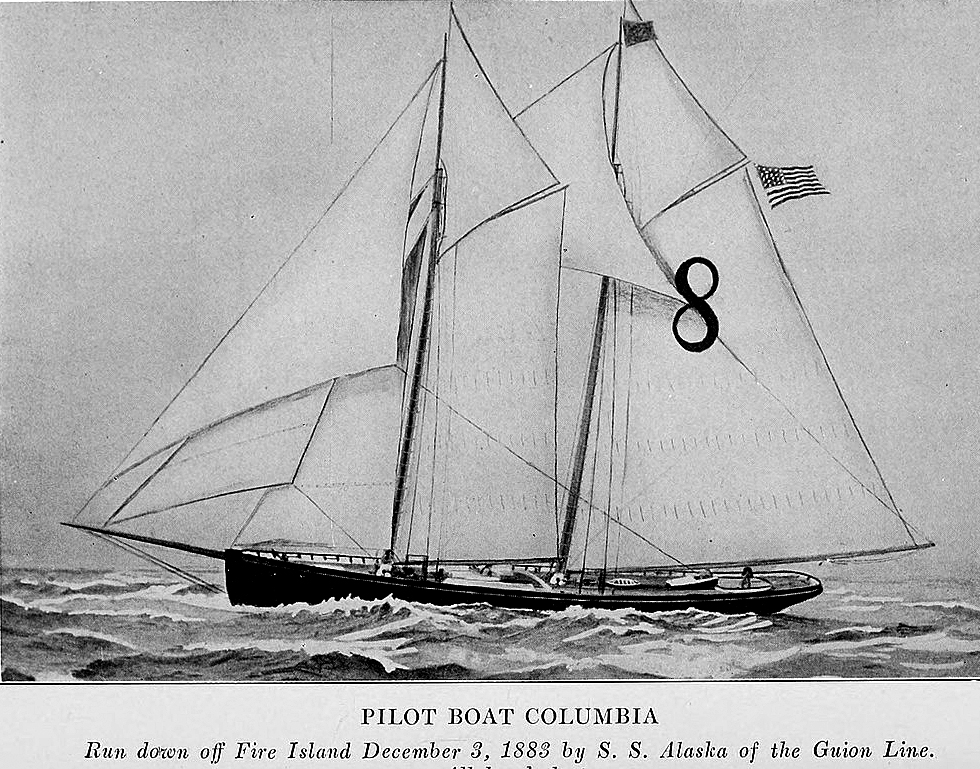

The pilot boat Columbia No. 8 had been built by C.R. Pollion and had been launched in 1879. The schooner-rigged pilot boat was eighty-seven feet overall with eighty-two feet at the water line. She had a twenty-one foot beam and had a mainmast of seventy-five feet, a foremast of seventy-three feet, a maintop mast twenty-eight feet and a fore top mast of twenty six. She was sixty-five tons burden and was owned by a conglomerate of sorts including Augustus Van Pelt, Henry R. Sequin, Christian M. Wolfe , the orphan children of Benjamin Simonson and the wife and children of Captain Stephen H. Jones, who had sadly dropped dead of a heart condition a year earlier. Aboard the pilot boat were four pilots, one pilot apprentice and nine additional crewmen. The weather conditions had deteriorated, but the S.S. Alaska required pilotage for the last leg of its transatlantic voyage. The pilots and crew aboard the pilot boat Columbia No. 8 readied on deck for their approach. The gale weather conditions did little to nullify the already dangerous duty of the pilots. Attempting to maneuver with the wind in a pitching sea coupled with the looming leviathan of steel was not for the faint of heart. The sturdy and hearty pilot boat Columbia No. 8 sliced through the choppy seas and her crew were reminded of the scrapes she had been akin to during her time at sea and on dangerous duties.

Born out of tragedy, as she had been launched to replace the lost Isaac Webb, pilot boat No. 8, which had been wrecked along the Quonochontaug Beach in July 1879 in dense fog, the Columbia No. 8 had her first brush with potential death to her pilots and crew in early February 1880. In a heavy gale, the S.S. Arizona, of the Guion Line, was off the Highlands from her transatlantic voyage from Queenstown when the Columbia No. 8 signaled its intent to send aboard a pilot. Though pilot Wolf was boarded safely aboard, the two crewmen in the yawl were tossed into the torrent when their yawl was capsized after the transfer. Captain Price, master of the S.S. Arizona launched a longboat from his charge to assist the stricken men. The Columbia No. 8 sent out a second yawl to also render aid to their boatmen. Though all the men were ultimately pulled to safety aboard the S.S. Arizona, the near loss of several of her men had been an early occurrence and illustration of her dangerous duty on the high seas.

In March of 1883, the Columbia No. 8 had another brush with disaster. After being towed back to New York, her captain and crew offered insight into their badly damaged vessel. While forty-five miles south-east of Sandy Hook, while attempting to assist the S.S. Rotterdam of the Netherlands Mail Line, the Columbia No. 8 was struck on the starboard quarter by the steamship. In addition to tearing off her main mast and railings, two of her hull planks were heavily stoved in. The collision with the steamship sent the pilot boat to dry dock for repairs. Months later, the repairs and her hearty band of pilots and boatmen would be tested when approaching the S.S. Alaska.

Meanwhile aboard the bridge of the S.S. Alaska, Captain Murry kept a watchful eye on the pilot boat’s approach. Captain Murry ordered the engines slowed and by midnight, the engines were completely stopped. The pilot boat Columbia No. 8 neared the liner. Captain Murry watched as the pilot boat, instead of staying in the lee, quickly crossed before the bow of the liner. “My God,” he paused for a brief moment and then continued, “what is that man going to do?” He yelled for the engines to be reversed. The single screw of the S.S. Alaska cavitated as it began slicing through the stormy conditions. Suddenly the heavy steel bow of the liner slammed into the pilot boat Columbia No. 8. Within seconds, the pilot boat and her crew of fourteen men vanished into the abyss.

Captain Murray immediately ordered one of the liner’s boats lowered as he dashed to the starboard side of the ship. His officers and crew began throwing heaving lines and buoys into the wind-whipped maelstrom of the gale. The last vestiges of the pilot boat’s rigging and mast were briefly spotted before being sucked into the black cauldron of the ocean. The men aboard the liner’s long boat fought against the torrent to the windward side. Splashed with the frigid waters of the Atlantic, they scanned the darkened waters for survivors. The water was eerily silent as if the voices of the pilots and crew had almost instantaneously been silenced forever more.

After an hour had passed with no survivors found in the water, Captain Murray ordered the longboat and his men retrieved with the davits. A small speck of light was identified in the distance and he ordered the helmsman to alter course. With the engines engaged, the light proved to be one of the buoys thrown overboard by the crewmen of the S.S. Alaska. Possibly, Captain Murray thought, someone was still alive. The longboat was again lowered, with a new crew, to search the area around the collision. Like their brethren crewmen, they found nothing.

At daybreak, Captain Murray and his men again scanned the horizon for any sign of life. It was nearly inconceivable that anyone could have survived the night in the frigid December seas. The S.S. Alaska’s course was set for Sandy Hook, New Jersey and the mighty liner’s engines were engaged on the next leg of the journey. Solemnly, Captain Murray, his officers, and crew, knew that the pilots had met their maker. What they didn’t know was the identity of the pilot boat that had suffered its deathly fate under their bow. Nor did the pilot commissioners of New York.

The office of the Pilots Commissioners was a confused and hurried place. News filtered in with each edition of the daily newspapers and from the haggard and tired pilots returning to the port from their duties. Journalists lurked about the dark halls of the office amidst the woeful and whimpering wives of the pilots of the various boats that had been out in the terrible storm. Children no more than knee high scampered about wistfully unaware of the tragedy that may have befallen their fathers upon the high seas. Misinformation was peppered amidst the conversations. Only time would tell which boats returned and which boat had been lost at sea. The commissioners had believed that it was either the No. 1 boat, also known as Hope, or the No. 8 boat, Columbia. As the light of the short December day began to wane across the yardarm, the bulk of the pilot boats had been accounted for by reports. The elder pilots and the commissioners spoke in low tones and managed the reports as they filtered in like single grains of sand slipping into an hourglass of the unknown and the known.

Meanwhile, Captain Murray, the S.S. Alaska finally docked in New York, called upon Mr. Andrew Underhill, the General Manager of the Guion Line. Captain Murray explained the horrible tragedy that had befallen the men of the unknown pilot boat. When questioned by reporters, Underhill defended the actions of Captain Murray. “From conversation with Captain Murray, I understand that the pilot-boat was intending to drop the yawl on the port side of the ship, so that it would pass close in under the lee, while the pilot-boat itself went to starboard. In that way both would drop astern together, with the yawl under the lee of the pilot-boat. The yawl capsized and the boat-keeper in trying to pick her up became confused and brought the pilot-boat under the bow of the ship. A heavy north-west gale was blowing, and it was a risky piece of maneuvering. Captain Murray could not have done more than he did, and I do not consider him in any way responsible.”

By December 5th, 1883, only the pilot boat Columbia No. 8 was unaccounted for. Flags aboard the pilot boats in New York flew at half-mast to display their mourning of their lost brethren. Dispatches received by the commissioners began to provide additional potential evidence as to the loss of the pilot boat. Off Fire Island, the location of the horrific collision, a fishing smack reported wreckage in the water. Men of the United States Life-Saving Service trudged along the south shore strands looking for any additional evidence of the wreck. None was located.

With heavy hearts, the pilot service had accepted the sad fate of the pilot boat Columbia No. 8. Once again, the pilots had suffered a deadly blow within their ranks. The Pilot Commissioners though knew that something had to be done to attempt to alleviate and minimize their dangerous duties on the high seas. Moving forward, they decided to inform all agents of the steam-ship lines that their vessels would have to come to a full stop prior to the boarding of pilots. Steerageway or any engine revolutions placed their pilots and their boats in danger, as sadly proven not only in the loss of the pilot boat Columbia No. 8, but also with other incidents of close calls with boats within the fleet. Additionally, the commissioners would also impress the importance of the steam ship officers and crews to assist in the boarding process when transferring from the pilot boat to the vessel requesting pilotage assistance. These combined efforts, the commissioners hoped, could help minimize the inherently dangerous work of the pilots.

In May of 1886, three years after the deadly collision, Judge Brown of the United States District Court found both entities at fault for the tragedy. His determination was that the S.S. Alaska had “starboarded her helm, she subsequently ported the helm, thus thwarting the expectations and maneuvering of the pilot boat, and the pilot boat” was equally responsible for the collision, “in crossing the bows of the steamship in such a gale.” Judge Brown “ordered a decree in favor of the libellants for one-half the damage sustained by the loss of the pilot boat and the loss of support to the widows of the lost men,” with a court ordered referee to determine the appropriate amount for the families.

The loss of the pilot boat Columbia No. 8 was a tragedy that ultimately instituted change for pilots and the vessel’s requiring their services. While pilotage duties remain hazardous to this day, the loss of the pilots and the crew of the pilot boat Columbia No. 8 were a catalyst for change for the pilot service, a service that remains as vital today as it was in 1883, in our waters.

About the Author – Adam M. Grohman is the researcher and author of over thirty-six books which capture the rich history of our maritime environs and United States Coast Guard history. For more information about scheduling a lecture or to purchase any of his available titles, please visit www.lulu.com/spotlight/adamgrohman or email grohmandive@hotmail.com.