Captain Noah H. Moore struggled with opening the hatch as he entered the bridge. The fifty to sixty mile an hour rain-soaked winds whipped along the bridge wing. Finally able to pull the hatch shut behind him, he reached up and pulled off his soaked sou’wester. The towline, which he personally inspected, was holding for the time being. As Captain Moore slapped the water from his cover against his oilskin pants, he contemplated the towline. How long, he wondered, would the towline hold under the terrible strain of the wind and seas? Captain Moore took his free hand and slicked back his hair and then donned his cover again. As he looked around at the officers and crew on the bridge, he realized that they were all asking themselves the same thing…for how long could the towline hold? The South Shore, being towed southward to her new owner, was being dragged, as if by the Devil himself, through the very worst of Mother Nature’s wrath. With no operating engine and limited electricity, Captain Moore and his men had no ability to maneuver through the buffeting walls of seawater or to place her bow into the seas and wind to fight the raging torrent. The South Shore and her skipper and crew were shackled to a single line from the tugboat which was barely able to be seen in the distance. The single towline was the lifeline of their survival. The South Shore was a dead ship.1 Captain Moore and his men were its captives.

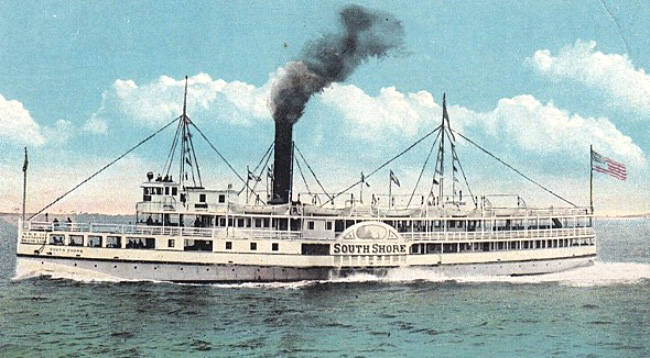

Nearly twenty-two years earlier, in June of 1906, the two hundred and seven foot in length sidewheel steamer had been delivered to the Nantasket Beach Boat Line. Built by the master builders at the Fore River Shipyard, she was a beautiful vessel complete with staterooms, a dining room, and a spacious area for an orchestra. Setting out each morning from Rowe’s Wharf in Boston, Massachusetts, she ferried guests from Boston to Plymouth, Massachusetts, daily during the season. She was a staunch and powerful steamer that would serve for many years on that daily routine. By the mid-nineteen twenties though, she had begun to show her age. Ownership passed through a few sets of hands and finally, in the middle of September of 1925, she had finished another summer season. Now owned by William M. and Andrew H. Mills, conducting business as the Mills Brothers Company, the South Shore and seven other vessels were tied up at a dock in Newark, New Jersey. The Mills Brothers had contracted with city officials for dock space for the winter with the provisos that the city would assume no responsibility for the safety of the vessels from September through May 15, 1927, the brothers would provide watchmen at their own expense, and that the vessels, if requested by the city, would be moved sooner if necessary. The Mills Brothers entered the contract and paid the City of Newark the contractual sum of six hundred dollars.

Less than a month and a half later, the South Shore, which had been reported as seaworthy and in sound condition, began to slowly fill with water. By the following morning, the South Shore had sunk at the dock and had inadvertently blocked the head of the channel. The City of Newark contacted the Mills Brothers and told them to remove the South Shore. The Mills Brothers simply ignored the city officials. The South Shore languished at the head of the channel. City officials were not happy with the Mills Brothers.

Several months later, on March 15, 1927, the Mills Brothers formally abandoned the South Shore. With each passing day, the steamer lost value, and the city officials began to lose their patience. The Mills Brothers were notified that the city had solicited a bid for the refloating and removal of the South Shore. The defiant brothers once again replied that they had abandoned the steamer. The lowest bid was twenty-two thousand dollars. The City of Newark awarded the contract, and the South Shore was subsequently raised. In the interim, the Mills Brothers had received their insurance payout on the sinking of the steamer and refused to pay for the refloating and salvage operation. The City of Newark officials filed a suit against the defiant brothers. While the court system addressed the liability of the sunken steamer and its subsequent salvage between city officials and the Mills Brothers, the South Shore was purchased by a new owner who needed a steamer for his operation in the waters of Baltimore, Maryland. His name was Captain George Brown.2 For seventy-five thousand dollars, the South Shore had once again changed hands and ownership.

In late April of 1928, the South Shore, in need of repairs, was on her way to her new owner in Baltimore, Maryland. The skeleton crew aboard, under the command of Captain Moore and six others, were now aboard amidst a horrific gale that had risen from the depths of hell two days earlier. The snapping of the towline had left the South Shore in a precarious position. Captain Moore and his men contemplated their escape as the steamer quickly careened toward the shoreline. Captain Moore and his men decided to abandon the stricken steamer. Braving the towering waves and wind, Captain Moore and his men alighted to the lifeboat davit. Five of the seven men boarded the lifeboat and two remained on deck as it began to be lowered into the maelstrom. Finally reaching the swirling seas, the lifeboat was quickly capsized by a wall of seawater. The five men, including Captain Moore, Chief Engineer Allen, and William Hicks, a quartermaster, were tossed into the stormy surf. Two of the men were able to fight bravely to the safety of their shipmates still aboard the steamer. They were dragged back aboard. Captain Moore, Allen and Hicks simply disappeared into the sea.

As the wayward steamer slammed against the bar off Morris Avenue, Captains Richard Hughes and Harry Yates, lifeguards of the Atlantic City Beach Patrol, rowed through the towering surf and removed the four crewmen from the beaten decks of the South Shore as it slowly broke apart amidst the storm. The four survivors were quickly rushed to the Atlantic City Hospital where they were treated for submersion, shock, and exposure. Later the same day, Captain Moore’s lifeless body was discovered on the hard-packed sand of the barrier island’s storm-strewn strand. Further offshore, and within sight of land, the South Shore slowly continued to break apart, her time at sea having come to an unceremonious and deadly end due to the wrath of the horrible storm and her parted towline.

Five months after the tragic deaths of three of her skeleton crew on her southern towing evolution to Baltimore, Maryland, the South Shore’s legal entanglement for the Mills Brothers and the City of Newark came to a decision in the District Court of New Jersey. On September 18, 1928, the request for exoneration for the Mills Brothers from the twenty-two-thousand-dollar salvage bill, was finally decided in their favor. Based on legal precedent and basic contract language, the City of Newark had lost its case. The contract terms did not address who was liable for the removal of one of the tied-up excursion boats if it sank at the dock. Had the simple provision been included in the contract, the Mills Brothers would have been contractually obligated to pay for all costs associated with the salvage and removal of the sunken steamer. As noted by District Judge Bodine, who agreed with arguments and precedent from an earlier case of the Irving F. Ross Petition of Ross Towboat Company, and as noted in his formal decision, “the sinking of the vessel at the wharf, and the consequent blocking of navigation, was one of those tortious wrongs for which Congress gave the shipowner the protection of the limitation of liability proceeding.”

The South Shore’s first sinking in October of 1925 had cost the City of Newark myriad headaches, legal enmeshment, and twenty-two thousand dollars in salvage fees. Sadly, the beaching of the South Shore on April 28, 1928, due to her parted towline in the middle of a terrible gale along the shoreline of Atlantic City, New Jersey, had an even heavier toll on the families of the three men who were lost when they tried to escape the stricken steamer in a lifeboat and drowned when it capsized, in our waters.

1 Though retaining her original name of South Shore for the duration of her career, the steamer was also referred to as the Atlantic Beach Park based on the wording noted on the port and starboard side of her bow.

2 Captain George W. Brown, originally from North Carolina, was an entrepreneur who established a black owned and black operated excursion business for black patrons in Brown’s Grove, in Maryland. Utilizing his own steamers, he was successful in transporting over 3.5 million visitors to the eastern seaboard get-away from 1906 to 1935. The loss of the South Shore was a terrible business and personal tragedy to Captain Brown as he had invested 75,000.00 to refit the South Shore and had planned to utilize the steamer for his upcoming summer venture. More importantly, the three men lost in the storm had been hand-picked by Captain Brown for the towing operation. As noted in the Afro-American newspaper on May 5, 1928, “Although the loss of the South Shore will necessitate the cancellization (sic) of all excursions to Brown’s Grove this year, he will not give up but will start plans to obtain a new boat for next season.” Captain Brown passed away in 1935.

About the Author – Adam M. Grohman is the researcher and author of over thirty-six books which capture the rich history of our maritime environs and United States Coast Guard history. For more information about scheduling a lecture or to purchase any of his available titles, please visit www.lulu.com/spotlight/adamgrohman or email grohmandive@hotmail.com.