The S.S. Mirlo trudged slowly through the calm waters off of North Carolina on her northbound course. With her tanks full of refined oil and gasoline, the British flagged tanker had set out from New Orleans, Louisiana six days earlier. Bound for New York and then onto England, her cargo was vital for the war effort in Europe. As the tanker steamed northward at her maximum speed of eleven knots, Captain William R. Williams and his crew of fifty men were well aware of the looming threat that lurked beneath the surface. All aboard were hopeful but cautious at the reality that they were most likely in the clear view of the enemy submarines reported to be operating in the vicinity. Despite the danger, the shipment had to get through to Europe if the allied forces were going to defeat the Germans. Captain Williams ordered extra lookouts posted on all quarters in hopes that if she were targeted, the officers and crew might have a few precious moments to take action. With limited armament to fight off an attack, the S.S. Mirlo was nothing more than a floating powder keg.

As Captain Williams paced the bridge of the S.S. Mirlo, in the distance Kapitanleutnant Otto Droscher peered through his periscope. Just a few moments earlier, Droscher and his crew aboard the U-117 had been actively laying mines into the sea lanes. At the first sight of smoke from the tanker’s stack on the horizon Droscher and his crew sealed the conning tower hatch and slipped beneath the surface and into obscurity. The submariners waited in the silence as Droscher stood peering through the periscope and quietly whispered orders to his helmsman and crew. Meanwhile, the helpless prey continued to steam toward them on the surface. Kapitanleutnant Droscher maneuvered into position to try and strike a lethal blow to the tanker. Droscher raised his right hand off of the periscope handle. Suddenly, he lowered it. “Feuer, eins!” Seconds later, the deadly torpedo sliced through the water toward its target. With the first torpedo racing toward the tanker, Droscher lowered his hand again, “Feuer, zwei!” Another torpedo rocketed toward its prey.

Captain Williams and his men had only seconds to try and mitigate the inevitable. The torpedo slammed into the aft starboard quarter of the S.S. Mirlo. The entire tanker shuddered violently. A huge plume of water rocketed skyward. The strike had been lethal and almost instantly plunged the ship into darkness. Seconds later, the second torpedo slammed into the stern. Despite his initial efforts to try and beach the stricken tanker, Captain Williams knew that his ship was mortally wounded and she began to sink. Captain Williams stoically ordered his men to abandon the tanker as fire and flames quickly engulfed the tanker’s decks and cargo holds. The crewmen raced to their lifeboat stations and three boats were quickly lowered into the swirling, flame-swept, swells. Hopefully, they believed, they would be able to reach the coastline unscathed.

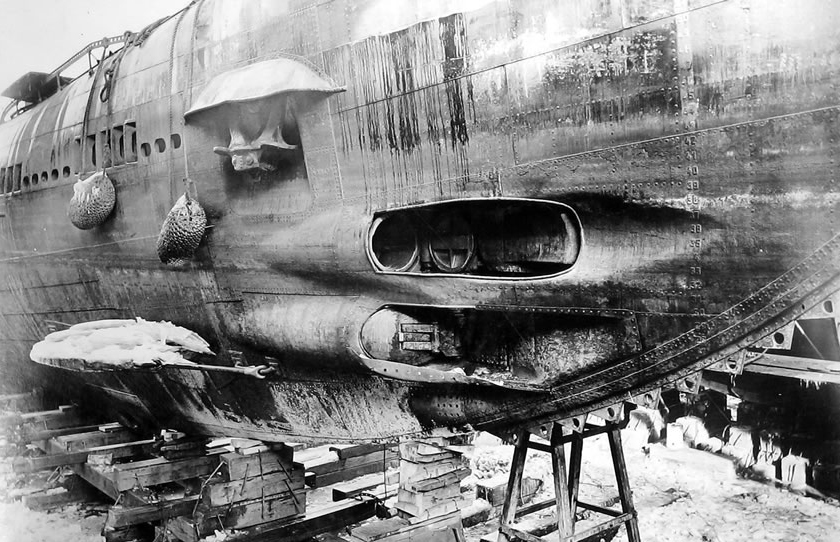

For the submariners aboard the U-117, their patrol thus far had been very successful. The sinking of the S.S. Mirlo was yet another conquest of tonnage to be added to their war chest of death and destruction upon the high seas. The U-117, a German Type UE II Submarine, had been designed as a coastal mine-laying submarine. The deadly underwater hunter was two hundred and sixty-seven feet, five inches in length with a beam of twenty-four feet four inches. Capable of roughly fifteen knots on the surface, she could make a top speed of seven knots while submerged and operating on her electric batteries. With a range of roughly fourteen thousand nautical miles she had extended the German Navy’s hunting grounds to include the heavily transited merchant sea lanes along the eastern seaboard of the United States. In addition to forty-two mines, she was armed with fourteen torpedoes. On deck, she was armed with a SK L/45 deck gun.

Under the command of Kapitanleutnant Droscher, the U-117 had set out from Kiel on July 11, 1918. The submariners tracked several vessels crisscrossing the Atlantic Ocean but due to inclement conditions, they had to watch the vessels steam away unscathed. Undeterred, Droscher and his fellow officers and crew pressed westward to the coastal waters of the United States. By August 8th, 1918, the U-117 entered American waters. With improved weather, the hungry hunters finally found the first of their prey – a pack of fishing vessels on August 10th. After allowing the fishermen to escape to their dorries and lifeboats, the submariners sank nine fishing vessels with her deck gun and explosives. Two days later, she pounced on the S.S. Sommerstadt. Initial plans to sink her with explosives and her deck gun were quickly aborted when it was determined that the steamer was armed. A single torpedo from the U-117 was utilized and its destructive force sent the steamer to the bottom. The reign of death and destruction by the U-117 had only just begun.

On August 13, 1918, the U-117 encountered the United States flagged tanker ship Frederick R. Kellogg in the waters off of Barnegat Light, New Jersey. The Kellogg was severely damaged and the U-117 began laying mines in the nearby waters. Droscher and his fellow submariners continued on their warpath across the waves the following day when they came upon a schooner. While attempting to send the schooner to the bottom, a United States Navy seaplane roared overhead. Droscher ordered a crash dive to escape the inevitable depth charges from the pursuer. Joined by a United States Navy submarine chaser, SC-71, the submariners dove deep to avoid certain doom. Amidst the depths, the U-117 avoided any significant damage and continued on her stealth patrol.

On August 15th, clear of her attackers, the U-117 set out an additional floating mine field in the waters off of Fenwick Island Light. Not as dramatic for the submariners as torpedoing a vessel, the laying of mines would still frustrate and destroy vessels that stumbled into them on the high seas. After navigating further south, a third mine field was set out by the U-117’s crew. After approaching the Madrugada, a sailing vessel, Droscher ordered her crew to abandon ship. Strafing the Madrugada with the u-boat’s deck gun sent the sailing vessel into the depths. An attack on another sailing vessel was thwarted by an approaching United States Navy seaplane. The U-117 dove into the depths and had once again avoided death from above.

Navigating further south, the U-117 was laying another mine field when they spotted a tanker in the distance. Two torpedoes had ignited the S.S. Mirlo into a fiery inferno. The U-117 set out one additional mine field and then, after consultation with his officers regarding their low fuel levels, Droscher ordered a course set to the fatherland on August 16th, 1918. Though the U-117 was forced to return to the safety of their own country, the submariners aboard the U-117 would continue on their piratical plundering of their unsuspecting prey as they plodded across the Atlantic Ocean.

On August 17th, the U-117 encountered and stopped the Nordhav. The linseed-laden, New York bound sailing ship was sent to the bottom with explosive charges. On August 20th, the U-117 engaged in a surface attack on a steamer but was unsuccessful in sending her into the abyss. Six days later, explosives sank the Rush, a United States flagged trawler. The Bergsdalen, on the following day, was the next victim of the U-boat’s wrath with a single torpedo shot slamming into her hull and destroying her. August 30th would see the end of the U-117’s reign of undersea terror with the destruction of two fishing trawlers, both flying the Union Jack, utilizing explosives.

Despite a near-crippling shortage of fuel aboard, Droscher attacked the War Ranee, also of British registry, on September 5th. The attack was unsuccessful and the ship steamed off to safety. Realizing that he would not be able to make the safety of port, the U-117 rendezvoused with the U-117 on September 12th to take on a transfer of fuel near the Faroe Islands. On September 22, with the assistance of a tug, the U-117 reached her homeport of Kiel. The late summer and early fall war patrol of theU-117 had come to an end. Though the U-117 would not again put out to inflict terror and destruction in the sea lanes, it would not be the last time the U-117 set out for the coast of the United States.

With the cessation of hostilities on November 11, 1918, the U-117 was ordered to be surrendered to the allied forces. On November 21st, the U-117 was surrendered without incident to the British Royal Navy in Harwich, England. The United States Government and the United States Navy however wanted several of the lethal hunters to chiefly support the nation’s victory bond drives and for naval engineers and designers to have a chance to investigate the surrendered technology. Under the command of Lieutenant Commander Aquilla G. Dibrell, the U-117 joined the small flotilla of war prizes and headed for the United States on April 3, 1919. Upon her arrival in the United States, theU-117 and the other war prizes proved to be popular exhibits aligned with the Fifth Liberty/Victory Loan Drive efforts. With the completion of the bond drive, the U-117 sailed for the Philadelphia Navy Yard where she was partially dismantled so that she could be researched and investigated by naval architects, submariners, and commercial submarine engineers and designers.

Though the U-117 was only able to complete one war patrol during the First World War, it marked a destructive and deadly toll on the merchant mariners and the United States Navy. The U-117 had successfully sunk twenty ships, damaged three ships and one warship during its patrol along the eastern seaboard. With the successful post-war tour and research by U.S. Navy officials in its wake, the rebuilt U-117 was finally set out for her final patrol. On June 21, 1921, three Felixstowe F5L flying boats, each laden with four one hundred and sixty-three pound bombs, began their bombing runs over the anchored U-boat. Though none of the bombs directly struck the U-117, the concussions from the cascading fusillade fatally rendered the infamous hunter prey. Her reign of underwater terror ended as the U-117 slowly slipped beneath the surface on her last, unceremonious, dive in our waters.

Sources

Columbia Daily Spectator.

“Aguilla G. Dibrell, USN, to Head ROTC Unit,” September 27, 1956.

Midgette, Don (LCDR, USCGR). “Captain John Midgett & The Mirlo Rescue.” www.ncgenweb.us/dare/photobios/mirlorescue.html.

U-Boat.net.

“U-117.”

“Otto Droscher” biography.

United States Navy. Naval History and Heritage Command. “U-117.” Washington, D.C.

United States Navy Department. Publication 1 – German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic Coast of the United States and Canada. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1920.