If you are not sure just what kind of barnacle is growing on the bottom of your boat or sticking like glue to your pilings, don’t feel inadequate, there are over 1,400 different kinds of barnacles growing in the waters around the world. Chances are they are the acorn barnacle. Better known among the saltwater crowd as “Crusty Foulers.” No matter what name you know them by, they are a pain.

What exactly are barnacles? Often thought of as being related to snails, experts believe they are first cousins to crabs because they have such a similar body plan. If you have had the job of scraping barnacles off the hull of a boat that has been in the water too long, you know they have incredible sticking power. The tensile strength of the fast-curing cement they secrete is 5000 psi. Gorilla glue has a strength of 4,252 psi. Chances are the glue makers would like to know the scientific formula for barnacle glue.

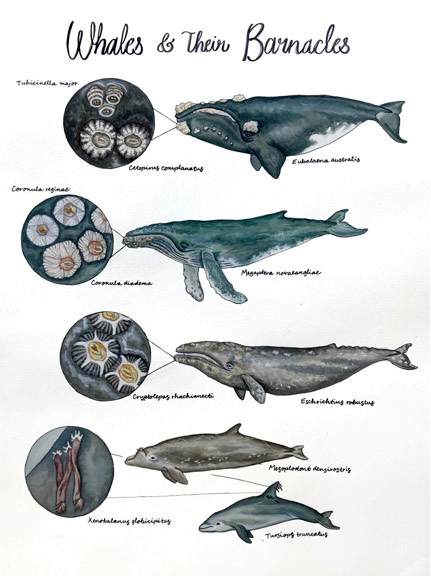

As annoying as it is to have scrap barnacles off the hull of your boat, think about the poor whales and dolphins that barnacles just love to stick onto.

Barnacles will stick onto a piling, an anchor, rocks, buoys, and moving objects like boats, whales, dolphins, manatees and other large fish. The U.S. Navy estimates that heavy barnacle growth on ships increases weight and drag by as much as 60 % which results in a 40% increase in fuel consumption.

The little buggers feed through a feather-like appendage called cirri. The cirri rapidly extend and retract through the opening at the top of the barnacle. They screen the water for tiny particles of food. If they sense trouble, they quickly retract into their protective shells. They are protected by calcium plates. When the tide goes out, the barnacles close up to conserve moisture. When the tide comes back in, they open to allow the cirri to reach out.

The experts believe the whale barnacles live on the whales for only a year with the whales shedding their barnacles at breeding time. Actually, there are six species of whale barnacles.

Oceana describes the acorn barnacle in this way “Acorn barnacles live along rocky shores throughout the north Atlantic and north Pacific oceans. Once an acorn barnacle attaches as an adult, it surrounds itself with a strong shell that provides it protection from predation and allows it to trap some water during low tide. Acorn barnacles live in the intertidal zone (the area between the high tide and low tide levels) and therefore needs to be able to survive long periods outside of the water. The shell can be closed tightly to prevent it from drying out. After they attach and build their little houses, acorn barnacles filter feed small plankton and other particles from the water using their modified legs.

The acorn barnacle mating system is very interesting. Adults are hermaphroditic – they are both male and female – but they cannot self-fertilize and must mate with other individuals to successfully reproduce. Like most crustaceans, this species reproduces via internal fertilization. For a species that includes individuals that cannot move, that can be a difficult process. Fortunately, individuals of this species have extremely long penises – the longest penises (relative to body size) in the animal world. While the adult body size is typically not larger than a half inch (1.25 cm), the penis can be three inches long (7.5 cm), six times the length of the body. Using this organ, individuals can pass and receive sperm to and from their neighbors. Individuals that are more than three inches away from any neighbor cannot reproduce. Even more interestingly, the penis dissolves at the end of the mating season and grows back each year.”

Just how do these barnacles get on the whale, to begin with? Adult whale barnacles are hermaphrodites. They fertilize the eggs of adjacent barnacles. The fertilized eggs develop into larvae which are then released into the water in the Hawaii wintering grounds. After further development as free-swimming larvae in the ocean, they can detect chemicals given off from a whale’s skin. These chemicals cue the tiny larvae to settle on and attach to a whale’s skin, metamorphose into juveniles, grow, and secrete incredibly sticky cement that tightly bonds them to the whale. Next, they begin to produce six vertical calcareous plates which will fuse to become the formidable circular shell within which the animal will live.

This shell is not solid material though. Cavities are built into the shell all around its circumference. These spike-shaped cavities pull “the whale’s skin into them as the shell grows. The whale and the barnacle shell are then almost locked together. Because this barnacle was broken in two, we were able (with the help of a Dremel tool) to see these cavities for the first time. And, as expected, they were filled with black whale skin! Skin also grows up around the base of the shell, leaving it firmly embedded and making it reportedly very difficult to dislodge.

Given that the barnacle animal itself is cemented to the whale and given the interlocking-shell-and-skin configuration, it is a wonder that they ever come off. But they do!

Well-known researchers Mark Ferrari and Debbie Glockner-Ferrari have studied humpback whales in Hawaii for 39 years. They have first-hand knowledge of whales losing barnacles while in their Hawaii breeding grounds. Mark recalls “that in 1987 they saw a yearling on separate occasions approximately a month apart. Because this individual was lethargic they were able to approach closely enough to actually see the barnacles and document their disappearance. He estimated that about 50% of the barnacles were lost during this time. And the reason they could tell that barnacles were being lost is that when a barnacle falls off, a perfectly circular scar is left.”

Acorn barnacles are not seriously threatened by people in any way. However, visitors to the rocky shore must be careful not to trample these animals during low tide. Try to avoid coming in contact with them since they can cause a nasty scrap.

One of the more interesting varieties is the gooseneck barnacle. What might appear to be dragon claws, actually they are not. They are what are known as gooseneck barnacles! These filter feeders are found in the rocky tide pools of Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary. Their shells are made up of multiple white plates that help protect them from predators and from drying out.

In fact, those simple little annoying creatures that stick to your boat hull are very complicated and you might say, a marvelous form of sea life, bless those little Crusty Foulers, annoying as they may be.