Unless your reading includes coastal shellfishing project news, mostly found in blogs, scholarly papers and trade journals, you may not have noticed the number of shellfish farms, mostly clam or oyster or a combination of the two, using bays and lagoons up and down the eastern seaboard. I read some of these publications, but it came as a surprise to see first an ad in Boats & Harbors and then another in National Fisherman announcing the sale of a Florida clam farm.

Doing a little catch-up reading, I found that since I had done an article on a new oyster business on leased Town of Islip bay waters, shellfish aquaculture has moved into the fast lane on the east coast from Maine to Florida. My reading was not only informative and interesting; it was a reminder that shellfisheries are a way to provide more food for an overpopulated world without the environmental pressures that come with other protein sources. The blue foods (what trendy types call aquatic protein) will become our go to food source while protecting the environment.

In warm states like Florida, clams can mature faster while the harvest takes longer up north. It still has to be profitable enough that the northern farms stay in business. The process ranges from twelve to forty-eight months, depending on location, desired market size and water temperature. The Gulf of Florida has the temperature for the fastest growth.

What has made clam farms popular in Florida dates back to the mid-1990s when the State of Florida outlawed gillnetting, leaving commercial fishermen unhappy, unemployed, high and dry. The State retrained the fishermen who were interested, teaching them how to put a clam farm together and run it. After their clam farmer training, Jonathan Gill and Shawn Stephenson started farming with a lease, bought some clams, planted them, harvested clams, sold them, repeated the process until their business got so big, they overwhelmed their local wholesaler with clams. That’s when they bought Southern Cross Sea Farms.

How does clam farming work? It starts with the hatchery. Clam larvae are placed on a fine screen and later moved as they grow, to algae rich water that is pushed up through the clam seeds that promote faster growth through continuous feeding. After about six months in the hatchery and nursery, the clam seed is transferred to nursery rafts out in the bay in mesh bottom bags. At this point, the bags are suspended from the rafts and the seedlings are able to eat what comes by. Once planted in the Gulf, the clam seeds start digging their way down in the bag and use their siphons to access food at the top of the bag. They keep eating and growing until they reach the 7/8” to 1” optimum size to sell.

Gill and Stephenson’s Southern Cross works with four boats and a crew to take care of their thirty leases that cover more than sixty acres in the Gulf. They use old flat-bottomed boats from their gillnetting days with electric winches that bring up the heavy bags of clams. The water surrounding Cedar Key is loaded with an alga that looks like dinner to the clams. Southern Cross has started aqua culturing oysters and their hatchery produces spat for other oyster farmers. They feel it takes as many work hours to take care of one million oysters as it does for ten million clams.

A larger clam farm in Georgia, Sapelo Sea Farms and Phillips Seafood, started in the late l990s when Charlie Phillips was approached about developing clam beds on a 1,000-acre parcel of tidal flats. Close to Townsend, Georgia, the clam farm is surrounded by bird preserves and nature preserves. From that time forward Charlie has built one of the largest clam operations in the world, employing several dozen people to produce the twenty thousand pounds of clams he sells every week to markets in the US and Canada. They use so many mesh bags they make their own. Using an airboat that can navigate the flats of the tidal marshes, the bags of clam seed are distributed to the marshes where the clams grow. In six months, the clam seed bags will come back to be separated by size, re-bagged in larger bags and brought out to the flats to grow to market size.

A smaller clam farm, Two Docks Shellfish, in Bradenton, Florida on Tampa Bay, specializes in hard clams for local customers and restaurants. Run by perhaps the only clam farmer with a degree in aqua culture, Aaron Welch has a PhD in Ecosystem Science and Policy and teaches in the aquaculture program at the University of Miami.

What is it like to start up in a business you’re not familiar with in an area of the country you’ve never seen before with only the word “farmer” in common with your past and future work life? Andrew and Heidi Hiser came to Charleston, South Carolina from a traditional farm in central Illinois to see Toby Van Buren’s clam and oyster farm, Tobias Seafood. Van Buren wanted to sell to the right buyer and was willing to work with them to show them how to run the business and to introduce them to his customers. That was in 2013. Although everything about clam and oyster farming was totally unfamiliar to them, the couple felt the business would be a good fit. They have since 2013 not only learned how to run the farm, but they have also formed partnerships with other farms and acquired marketing skills to provide high visibility for their products at events such as the South Carolina Aquarium’s Oyster Fest. They are enjoying the personal relationships they have formed with customers and are looking forward to expanding their offerings to include shrimp and soft-shell crabs.

Their partner providing oysters for the Oyster Fest is St. Jude Farms: a young seafood aquaculture company that is growing triploid oysters. Relatively new in the south, triploid oysters have three sets of chromosomes and do not spawn, which promotes faster growth. Their mortality rates are lower than traditional oysters and they yield higher weights. As St. Jude increased their lease holdings, their employees noticed fields of wild growing mussels in their newly acquired real estate. They tried cooking the mussels with wine and garlic and found they had a winner. The new produce is a favorite at Bay Street Biergarten.

At the Cabretta Clam Company a former shrimper, Jeff Ericksen, has turned from offshore trips for shrimp to close by aquaculture farming. His leased space for clamming is an inland marsh along the Mud River not far from home. He traded a long trip for shrimp for a short trip for clams without giving up his lifestyle. He sells his clams to Sapelo Sea Farms and local restaurants. Learning the business from his brother who owns Sapelo, Jeff started out clamming and continued shrimping until his first crop of clams reached market size.

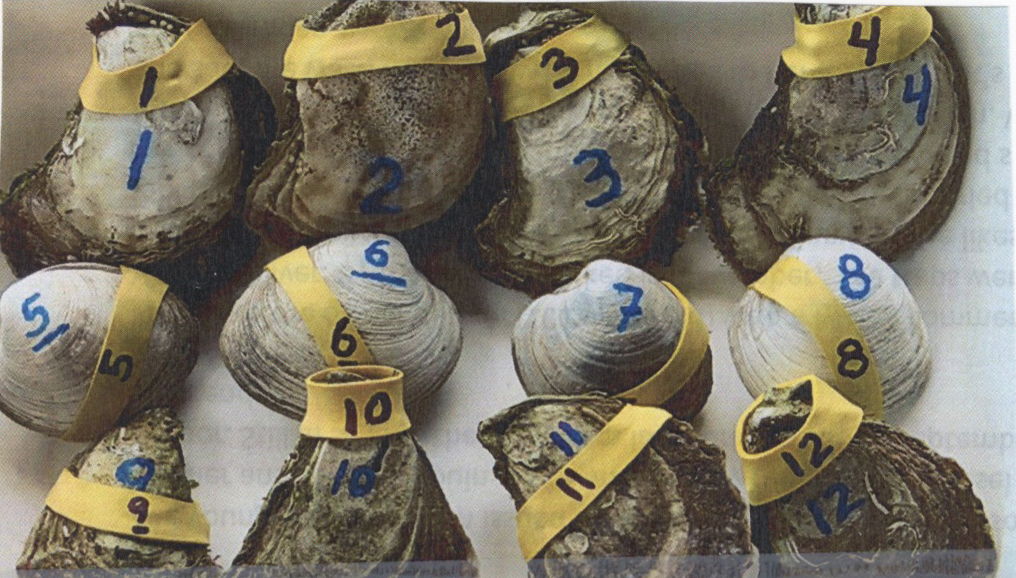

Not only can clams, oysters and mussels feed the hungry, but they also clean up the waterways by removing excess nitrogen. A single clam filters between five and ten gallons of water a day. An overabundance of nitrogen from fertilizer runoff and septic tanks promotes algae growth that reduces oxygen levels. As filter feeders these shellfish incorporate the nitrogen they filter out of the water into their shells and tissues as they grow. Adult oysters can filter up to fifty gallons of water a day. The Woods Hole Sea Grant and Cape Cod Cooperative Extension measured the shell samples of wild and farmed oysters and clams from various Cape Cod locations. Oysters averaged .28 grams of nitrogen in their shells and clams .22 grams. Wild oysters and those on pond bottoms had an average of.32 grams of nitrogen, which was attributed to the wild oysters having to deal with predators and growing harder shells to accommodate their needs.

Although many in the shellfish aqua culture business agree that it’s part art, part science, part trial and error and the rest luck, it seems to be working, especially in Florida. Not only did the state of Florida train the clam farmers, when COVID closed restaurants, the state came up in 2020 with their Clam Buyback Program and used COVID funding to purchase 450,000 oversized clams for a restoration project, helping the clam farmers survive and looking to the future in the Indian River Lagoon Restoration.