Early Life

Edward John Smith was born in Hanley, Staffordshire England on January 27, 1850. Smith went to the British School in Eturia Staffordshire. At 13 he left and operated a steam hammer. In 1867, he moved to Liverpool at age 17, following his half-brother Joseph Hancock, who was a sailing ship captain.

His apprenticeship was on the Senator Weber, owned by the Gibson and Company of Liverpool.

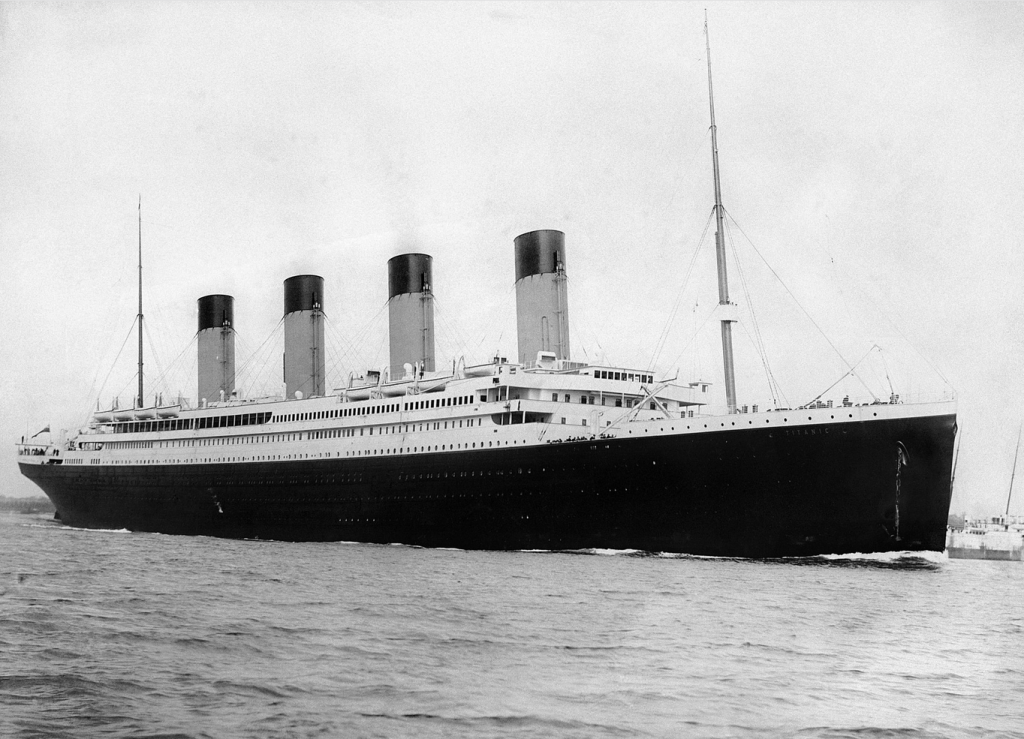

He was a British sea captain and naval officer. He joined the “White Star Line” in 1880 as an officer for the British Merchant Navy. In the second Boer War, he served with the Royal Naval Reserve, which transported troops to the Cape Colony. He served as captain of the ocean liner Titanic and went down with the ship.

Early Commands

During his time with the White Star Line in March 1880, he was the fourth officer of the SS Celtic. He served aboard the liners to Australia and then to New York. In 1887 he received his first command, the Republic. Smith joined the Royal Naval Reserves as a lieutenant. He received letters “RNR” after his name. It meant that he could be called to serve in the Royal Navy in times of war. In 1905 he retired from the RNR with the rank of commander. Smith was Majestic’s captain starting in 1895 for nine years. During the second Boer War in 1899, Majestic was called up to transport the British Imperial troops to the Cape Colony.

From 1904 he had command of the Baltic. It was considered then the largest ship in the world. She sailed from Liverpool to New York on June 29, 1904. Later, Smith was given another ship, the Adriatic. He received the Long Service Decoration for officers of the Royal Naval Reserve. Smith was again to take on a command of a lead ship in a new class, the Olympic. It had a maiden voyage from Southampton to New York on June 21, 1911. An incident happened while docking at Pier 59. One tug got caught in the backwash from the Olympic. The ship spun around, colliding with a bigger ship and became trapped under the Olympics’ stern but managed to work free. Olympics’ first accident happened during a collision with a British warship, the HMS Hawke. Damage to the Olympics’ compartments and one of the propeller shafts was twisted, but the ship made it back to Southampton.

The Royal Navy blamed Olympic due to her massive size which they felt generated a suction that pulled the Hawke into her side. This occurred on September 20, 1911. The incident became a financial disaster for the White Star, but the Olympic returned to Belfast for repairs.

In Feb of 1912, the Olympic lost a propeller blade and again had to have repairs. Harland and Wolff had to pull parts from Titanic for the Olympic which delayed the Titanic’s maiden voyage. Smith was asked to command the new ship in the Olympic class at the time. The Titanic left Southampton for its maiden voyage. In the Halifax Morning Chronicle on April 9, 1912, an article showed Smith in charge of the Titanic.

On April 10, 1912, Smith arrived on board at 7 am to prepare for the “Board of Trade” muster at 8 am. He went to his cabin to get sailing reports from chief officer Henry Wilde. During the first four days, no problems occurred, but on the 14th, Titanic’s radio operator reported receiving six messages from other ships warning of drifting ice. The crew aware of ice nearby did not reduce the ship’s speed and stayed at 22 knots (25mph). It was criticized that the continued speed was considered reckless, but at the time, was a common maritime practice.

Officer Harold Lowe reported the custom to “Go ahead” which depended on the lookout in the crow’s nest and the watch on the bridge and to be on alert was a standard procedure. Lowe reported he had never heard that icebergs were common off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Also, he didn’t know the Titanic was following a so-called “southern track” making a guess the ship was on a northerly one. North Atlantic liners insisted on time-keeping that would promise arrival time. The ships were frequently driven at full speed. It was believed that ice posed small risks.

In 1907, the SS Kronprinzwilhem, a German liner hit an iceberg receiving a crushing blow but completed the voyage. Smith felt he could not imagine any condition would cause a ship to founder. A short time after 11:40 PM on April 14th, the first officer William Murdoch reported the ship had collided with an iceberg. The ship was seriously damaged. The designer, Thomas Andrew reported the first five of the ships’ compartments were breached, and the Titanic would sink in under two hours. There had been different reports concerning Smith’s actions during the evacuation of the passengers. He did his best, some said. Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen from the Royal Canadian Yacht Club reported he did all he could to get women and children into the boats, and that they were lowered the correct way. A First-Class passenger also said that Smith was the biggest hero he ever saw. Smith was on the bridge using a megaphone making himself heard. Others had said he was ineffective as well as inactive in preventing loss of life. He had 27 years of command.

This incident was the first crisis of his career, and he would have known that even if all the boats were occupied, there still would have been more than a thousand people on board as the ship went down. During this time, he began to grasp what was about to happen. He appeared to have become paralyzed by indecision. He failed to order his officers to place the passengers into lifeboats and failed to organize the crew.

He never gave the command to abandon the ship. Some bridge officers were unaware the ship was sinking. Fourth officer, Joseph Boxhall did not find out until 01:15, an hour before the ship went down.

Quartermaster (supervises logistics and requisitions, manages stores or barracks, distributes supplies and provisions) George Rowe was unaware of the emergency, and after the evacuation started, he phoned the bridge asking why he had seen a lifeboat pass. Smith did not let his officers know the ship did not have enough lifeboats to save everyone. Not long before the ship began to plunge, Smith was still releasing the crew from their duties. He made a final tour of the deck. At 2:10 AM, Smith said on the megaphone for them to do their best for the women and children, as well as for themselves. This was the last sighting of Smith. A crew member Trimmer Samuel Hemming found the bridge empty. Within 5 minutes the ship sank beneath the ocean. Smith perished along with about 1,500 others.