On Sunday, June 2, 1918, a band playing “Where Do We Go from Here” marched along Atlantic City’s boardwalk, to the cheers of spectators. Then, as the band neared South Tennessee Avenue, the music came to an abrupt stop. The crowd’s attention had turned toward the sea. Pitching in the waves, a lifeboat loaded with twenty-five men and five women were approaching the beach. No one onshore had any idea what had happened. However, without hesitation, many in the crowd and members of the band ran directly into the water to help bring them to shore. It was only then that most learned of U-boat attacks, which had occurred so close to the Nation’s shores.

Despite news of the sinking of the RMS Lusitania in May 1915, with its loss of 1,198 passengers and crew, including 128 Americans, the U. S. remained neutral. However, following the U-boat sinking of ten U. S. vessels in European waters, between Feb 3 and April 4, 1917, the Nation declared war on Germany.

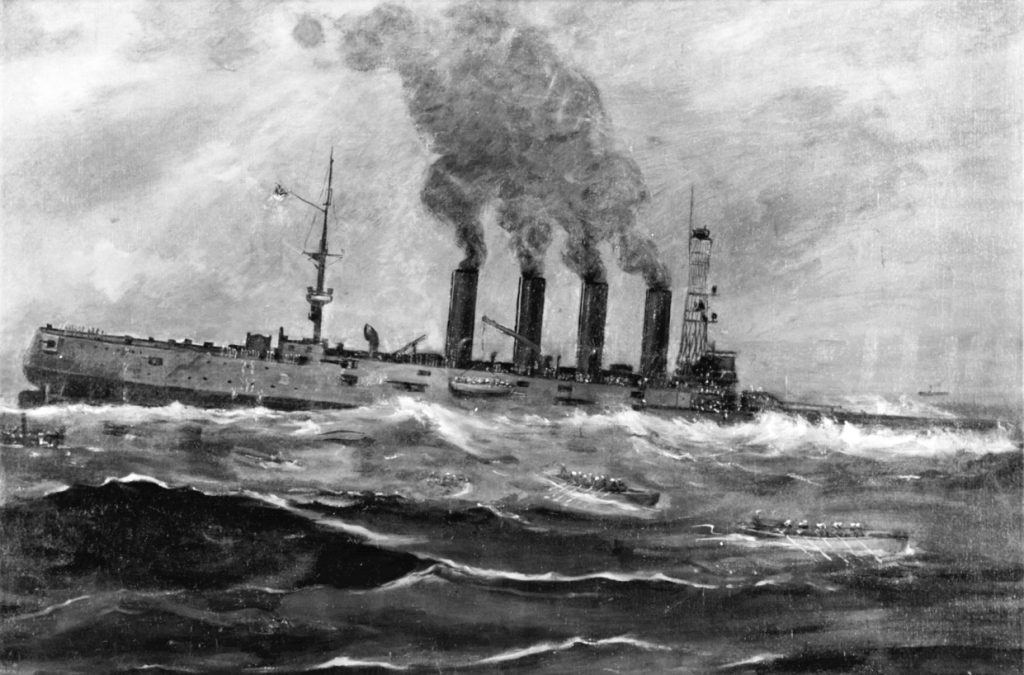

The 213-feet long German submarine, U-151, had a complement of 8 officers and 65 enlisted men. Armed with two six-inch guns, two 22-pounders, six torpedo tubes and 40 mines, it had a surface speed of 11.5 knots and submerged at 8 knots. On April 14, 1918, it set out from its home port of Kiel, Germany, toward the Atlantic east coast. It was the first attack submarine that would cruise our coastal waters. In mid-May, as it approached the coast, the U-boat laid mines, sank fishing schooners and cut two transatlantic cables with a device mounted on its deck. By May 21, there already had been several more reports of sightings and sinkings of American and Canadian vessels.

On the morning of June 2, U-151 managed to sink six ships in less than two hours. It included the cargo/passenger steamer SS Carolina, one of whose lifeboats had managed to land at Cape May. Enroute from San Juan to New York with 218 passengers, a crew of 117 and a cargo of sugar, the steamer intercepted an SOS call from the schooner Isabel B. Wiley. It was being attacked by a submarine. The vessel was only 13 miles away. The Carolina’s captain immediately ordered the shutdown of all of the ship’s lights and changed course. However, a short time later, the submarine was spotted, at a distance of less than 2 miles. U-151 fired a shot that landed astern, some 100 yards away. Two more shots were fired, both of which landed very close to Carolina. Located some 125 miles off Sandy Hook, New Jersey, the steamer’s engines were shut-down and the captain ordered the ship’s lifeboats lowered. Women and children were then boarded first. Once all of the lifeboats were clear, the submarine’s Captain ordered, in English, that they set out for shore. Once the lifeboats were clear, the submarine fired three more shots that sealed the fate of the steamer. It sank to the bottom to a depth of 250 feet.

As they headed toward shore, most of the lifeboats separated from the group. One of the lifeboats managed to get to shore at Barnegat Inlet, while the British steamship rescued 18 aboard another lifeboat. They were transported to Lewes, Delaware. Additionally, the lifeboat that landed at Cape May made it ashore. But, the occupants of one lifeboat were not as fortunate. Caught up in rough seas, the boat capsized taking the lives of the thirteen aboard.

The Captain of the U-151 was apparently careful not to harm the crews and passengers of the ships that were sunk by his submarine. However, that was not the case for most other German attack submarines, especially on the western side of the Atlantic. As the U-151 was approaching the American freighter SS Winneconne, it fired a shot across the freighter’s bow. A small boat launched from the sub made its way alongside the American vessel. The ship’s officers and crew were then ordered to board their lifeboats. When the freighter’s captain asked what was the reason that they wanted to sink his vessel; the answer was “we’ve got to sink you. War is war.”

U-151 returned to its home port on July 20th. Twenty-three vessels had been sunk, four of which were lost by mines deployed by the U-boat. Of all those ships lost, a total of 13 American crewmen had been lost.

About 15 days after U-151’s arrival on the east coast, she was joined by her sister ship, U-156. As U-156 cruised near shore, she laid a number of mines in approaches to New York Harbor. Most were located just east of the Fire Island Lightship (stationed off of Fire Island, NY). Submerged and sailing farther north, U-156 surfaced and, off Cape Cod, sank the tugboat Perth Amboy. In firing at the tug and her three barges in tow, some of its shells landed on a salt marsh. Nearby beach-goers were sent scrambling. Several aircraft and Navy submarine chasers were called up, but the submarine got away unscathed. The submarine then headed for the Gulf of Maine where it sank 21 commercial fishing vessels. As U-156 departed the Atlantic coast, three other U-boats arrived on the scene. However, making her way back to Kiel, U-156 met with her own fate. She struck a mine laid by the U.S. Navy in the north. The submarine sank to the bottom taking the lives of its entire crew.

The 503-feet long USS San Diego also fell victim to a mine. It was one laid by U-156 off Long Island. On Monday, July 8, 1918, after refueling at Portsmouth, NH, the warship cruised the Atlantic coast, enroute to New York Harbor. Ten days later, as it was passing Fire Island Beach, a massive explosion blew a hole, amidship, on her port side. As water rushed in, the wounded ship listed hard to port. In minutes, the captain ordered, “all hands abandoned ship.” Barely 28 minutes after the explosion, the San Diego sank to the bottom taking the lives of six of its crew. Lying upside down in 110 feet of water, 13.5 miles off Long Island, the wreck is a favorite scuba dive site. Exploring the wreck is not only a “dive into history,” it is a habitat rich in a wide assortment of attractive marine life. The USS San Diego was “the only major warship lost by the United States during World War l.”

Its location: Latitude 400 33’ 0.36 N, Longitude 730 0’ 28. 3896 W.