Ships have traditionally used ballast at the bottom of vessels to maintain their stability. The early forms of ballast included stones, gravel, sand, iron and eventually water. As a ship approached its destination, its hard ballast was unloaded to avoid possible grounding in the harbor’s shallower waters. However, loading and unloading solids or even water ballast has always been a threat to the marine environment. Organisms inadvertently taken on with the ballast at the port of loading are then transported and released at or near the vessel’s destination. Large ships are said to take on up to 20 million gallons of water at their loading port.

During the mid-1700s, near North Carolina harbors, underwater mounds of discarded ballast stone were building up and endangering approaching vessels. In response, the state’s General Assembly passed the 1784 act prohibiting disposal of ballast in the channels.

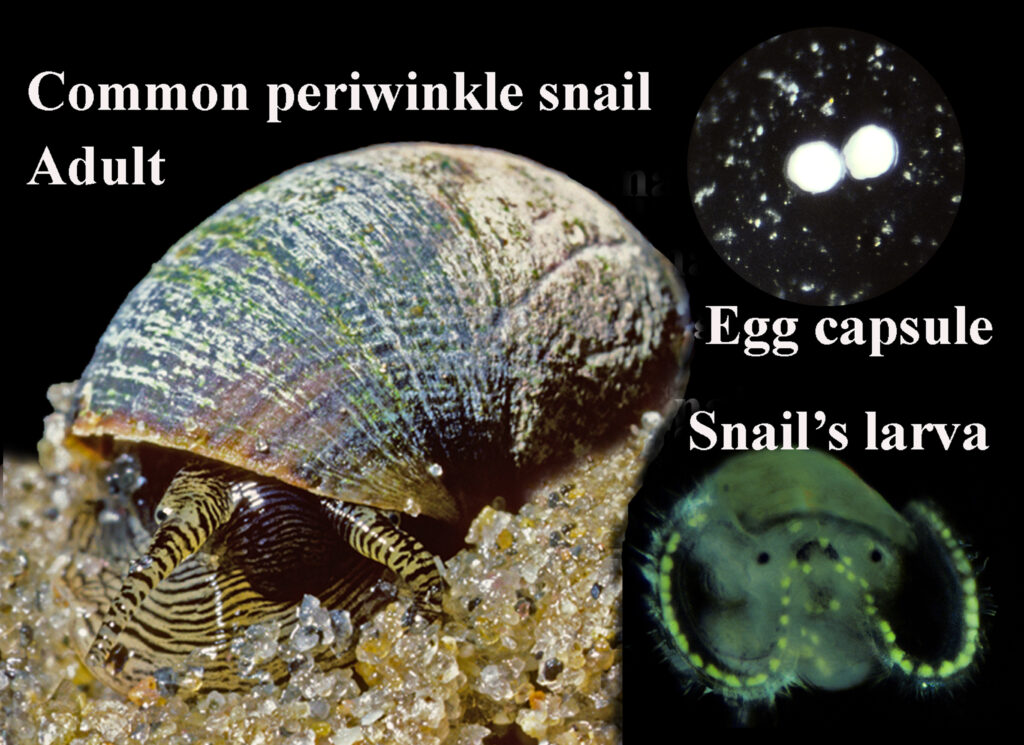

One of the earliest alien immigrant species introduced to our coast was the common periwinkle snail (Littorina littorea. .It was first detected in 1840, at Pictou, Nova Scotia. In England and at other European sites, the snail was an ancient food source. Was it intentionally transported to North America as a consumable or was it introduced mixed in with stone ballast or both? The jury is still out.

About a decade after first being sighted at Pictou, the snail was also found on the mud flats of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Aided by southern-flowing currents, its new home was the perfect location for launching an invasion of New England and the Mid-Atlantic states. During reproduction, the female releases tiny floating egg capsules that are carried by the currents. Within a few days, the eggs hatch as tiny larvae (veligers) that continue being carried to new sites by the currents. By 1888, some of the snails had established themselves on the shores of Cape May, New Jersey. It now ranges from Labrador to Delaware.

Beginning in the 1800s, solid ballast began to be replaced by water. Evidence of the discarded stone ballast is clearly evident in Savannah, GA. The source for its River Street, hand-laid cobblestone pavement, as well as some of its stone walls lining the streets, originated from European and/or African ports.

The switch to water ballast created a surge of invasive species. The liquid is a perfect medium for transporting and spreading a wide variety of foreign plants, marine life and fresh water organisms. It has been estimated that every day “7,000 species are carried around the world.”

Native to the European and North African coasts, the green crab (Carcinus maenas) was first encountered on the Massachusetts shoreline in 1817. By the early 1900s, it had spread northward and during the 1950s, it is believed to have contributed to the severe decline in Maine’s population of soft-shell clams. The crab can dig down six inches in quest of a clam. It “can consume 40 half-inch clams per day.” The crab has had a dramatic impact on other native species, including small oysters and smaller sized crabs. It was later reported on the marshes and shores of Nova Scotia to Virginia. It became the world’s most widely distributed invasive crab.

Other impacts created by invasive plants and animals include decrease of available habitat for native species, competition for food resources, decrease in water quality, cross-mating causing genetic dilution, introduction of parasites and disease carried by the alien and cost of control (“invasive species cost the U.S. more than $120 billion per year”).

By 2005, the US Fish and Wildlife Service identified a total of 91 invasive species in Long Island Sound. These ranged from alien sponge, barnacles, anemones, seaweed, marsh plants and a host of other introduced species. One of the more recent arrivals is the Asian shore crab (Hemigrapus sanguineus). In the Sound, it was first discovered in 1994 at Rye, NY. A native of China, Korea, Japan and Russia, the crab is now common from Maine to North Carolina. It is easily recognized by their olive-green color and white-tipped claws. Their shell (carapace) is only about three inches wide. Following its introduction, there has been a decline in Atlantic rock crabs, spider crabs and the non-native green crab. But one alien least likely to succeed in Long Island Sound is the lionfish. Between 2001 to October 2003, 11 juvenile lionfish were captured in lobster pots at the eastern end of Long Island Sound. Luckily, these waters are too cold for the fish to survive through the winter.

First sighted in 1985 at Dania Beach FL, south of Fort Lauderdale, the lionfish may have been deliberately released from a private collection or less likely, transported in ballast water. Several of the fish were apparently introduced during Hurricane Andrew (1992) when a private aquarium was flooded. In January 2018, Florida spearfishing scuba divers were enlisted in a lionfish-killing contest. Similar tactics have been employed for ridding the state of its most famous alien immigrant, the Burmese python. They can reach a length of 20 feet! Since 2000, more than 22,000 pythons have been removed from the Everglades. Still, it is estimated that “tens of thousands” continue to thrive in the National Park.

On 21 June 2012, the U.S. Coast Guard issued a new set of regulations for the discharge of ballast waters. The rules depend on the ship’s size and when it was constructed. Fines of $35,000 per day as well as criminal sanctions can be applied for violations of the rules. The new regulations can be reviewed online under USGS Ballast Water Regulations.

Private citizens can also help prevent the invasion of alien immigrants by destroying them and/or reporting sighting of any new alien species. Non-native pet amphibians, reptiles, fish and any other creatures including plants must not be released into the environment. Marine or fresh water weeds should also never be set free in the wild. To prevent aquatic hitchhikers, boats and boat trailers that are used between different bodies of water should be clean-dried. Unused live bait and the seaweed or other materials in which they are packed for transportation, should be disposed of in the trash.