The first I read about Sir Ernest Shackleton’s daring exploits was in the 1959 book Endurance, a New York Times best-seller, by Alfred Lansing. My mother, an avid reader said, “Greg, you must read this book. It’s a fantastic story,” and she was right.

The book is about Shackleton’s 1914 ill-fated Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, the goal being to cross the Antarctic continent from west to east. The expedition’s ship, Endurance, was trapped in the pack ice and crushed. Shackleton and his men had to take to the ice to survive. They drifted on the pack ice for over a year until finally, in a desperate bid, succeeded in reaching land, the unexplored and desolate Elephant Island. But that was just the beginning of the tale and it is one of the greatest adventure stories ever told.

I’ve always been interested in Arctic exploration and as it turns out Sir Ernest was probably a distant relative of mine on the Irish side of the family. Having this tenuous connection, I’ve followed many news stories about the great explorer. In 2022 the wreck of the Endurance was found two miles down at the bottom of the Weddell Sea in Antarctica 107 years after she sank. Recently I read that the wreck of Shackleton’s last expedition vessel, Quest, the one he died on, had been found. The two vessels couldn’t have been more different, but each was to suffer the same fate, sunk by ice. Originally named Polaris the Endurance was a three-masted barkentine built for polar bear hunting in 1912. Designed by Ole Aanderud Larsen, Endurance was built at the Framnæs shipyard in Sandefjord, Norway under the supervision of master wood shipbuilder Christian Jacobsen. Every detail of her construction was scrupulously planned to ensure maximum strength and at the time of her launch, she was arguably the strongest wooden ship ever built. Her keel members were made up from four pieces of solid oak adding up to a thickness of 7 feet while her planking was up to 30 inches thick and sheathed in greenheart. She had twice as many frames as a normal ship and they were double thickness. The bow was designed to meet ice head-on and had been given special attention, each timber had been made from a single oak tree. Her principal dimensions were length 144 feet, beam 25 feet, and 350 gross tons. Propulsion was provided by a 350-horsepower steam engine giving her a speed of 10 knots. She was altogether a much larger and more powerful vessel than the Quest..

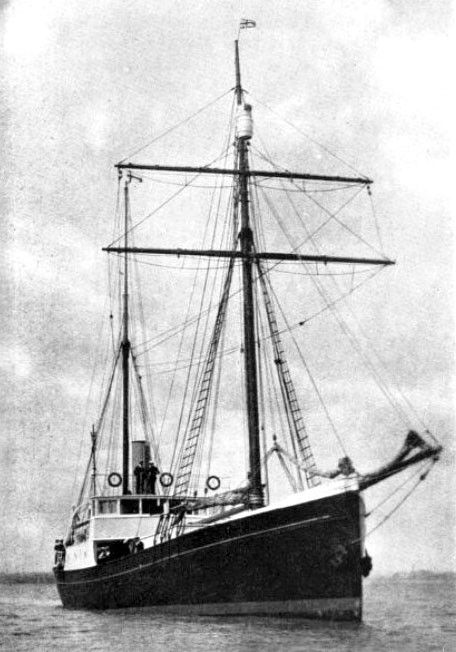

The Quest was a typical low-powered schooner-rigged steamship built for seal hunting. Originally named Foca the vessel was renamed Quest in 1921 by Lady Emily Shackleton, wife of Sir Ernest Shackleton. She was built in Norway in 1917 and hunted seals commercially. Although not designed for work in the ice she took part in many separate expeditions. During WWII she was requisitioned by the Canadian government to transport coal. The Quest’s principle dimensions were 111 feet in length, beam 24 feet, and 12 foot draft, 214 gross register tons.

The Shackleton–Rowett Expedition ship Quest set sail from London on September 17, 1921 bound for Antarctica. The Quest reached the harbor of Grytviken in South Georgia on January 4, 1922. The following night Shackleton summoned the ship’s surgeon to his cabin complaining of chest pains, he died of a massive heart attack aboard the vessel, he was 47 years old. At the request of his wife, he was buried on the island of South Georgia where years earlier he had crossed the mountainous interior to help rescue his crew that was stranded on Elephant Island.

This ended the expedition’s original program of exploring the Antarctic coastline of Enderby Land. Quest did carry out a short survey of the Weddell Sea area before returning to the South Atlantic. The expedition returned to England in July 1922 having posted disappointing results. One of the main problems was the Quest’s poor performance in polar sea ice. The vessel’s straight stem and weak engine made her unsuitable for use in icy seas.

The Quest was refitted for sealing in Norway in 1924 and the deckhouse, that Shackleton had added, was salvaged for shore use. In 1928 the vessel took part in the effort to rescue the survivors of the Italia Arctic airship crash. In 1930 the Quest served as the primary expedition vessel for the British Arctic Air Route Expedition led by Gino Watkins and later was the expedition ship of Count Gaston Micard’s East Greenland expeditions between 1932 and 1936.

The aging sealer was refitted and returned to sealing in 1946. On May 5, 1962 while on a seal-hunting expedition off the northern coast of Labrador, she was trapped in ice. Her hull was pierced by ice, and she sank off the north coast of Labrador. The entire crew was rescued.

John Geiger, CEO of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, led a team of international experts including shipwreck hunter David Mearns to search for Shackleton’s last ship. Geiger is quoted as saying, “Shackleton was known for his courage and brilliance as a leader in times of crisis. The tragic irony is that he was the only death to take place on any of the ships under his direct command.”

Shipwreck expert Mearns said, “I can definitively confirm that we have found the wreck of the Quest. Data from high-resolution side-scan sonar imagery corresponds exactly with the known dimensions and structural features of this special ship and is also consistent with events at the time of the sinking.”

The discovery of these two shipwrecks tells a story of one man’s quest for greatness. His men called Shackleton, “The greatest leader that ever came on God’s earth, bar none.” Another contemporary said, “For scientific leadership give me Scott; for swift and efficient travel, Amundsen; but when you’re in a hopeless situation when there seems no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.”

During all his great adventures and despite almost insurmountable odds Shackleton never lost a man on any of his expeditions. He was loved by his men and considered by many to be one of the greatest polar explorers of all time.