Exploring the beach this past winter, I came upon parts of a mid-19th-century wreck at Jones Beach. While researching the wreck of the Montezuma off Long Island’s famous Jones Beach on May 18th, 1852. I became intrigued by the fact that this ship was built in a large shipyard in Lower Manhattan. Fortunately, all 500 immigrants and crew were saved. The wrecked ship then sank into the surf, seemingly forever. Before this disaster, it broke speed records from Europe to America.

The Montezuma was a packet brigantine built in Manhattan in 1843 by Webb & Turner Shipyard on the shore of the East River between 4th and 5th Streets and Corlear’s Hook, where today is New York City’s Corlear’s Park. In this location, 135 major ships from 1825 to 1869 were built under the names “William & Allen” and later under his son, as the “William F. Webber Shipyard.” I was amazed that such a large shipbuilding enterprise existed in Lower Manhattan at any time in history. In the early days, it was William’s father, Henry, who was the master builder. William, meanwhile, went to Scotland to the famous shipyards at Clyde to study shipbuilding after a six-year apprenticeship in America. When he finds out that his father tragically died at 46, William rushes home to take over his father’s shipyard, and when examining the books, he discovers it to be insolvent. He devotes time to paying off his father’s debts, which was the honorable thing to do. Today, all efforts would be made to stiff everyone, you can bet on that. Then he set about changing the name to “William H. Webb Shipyard.”

During the years from 1840 to 1865, he built a very successful business and built 133 vessels right on the banks of Manhattan Island.

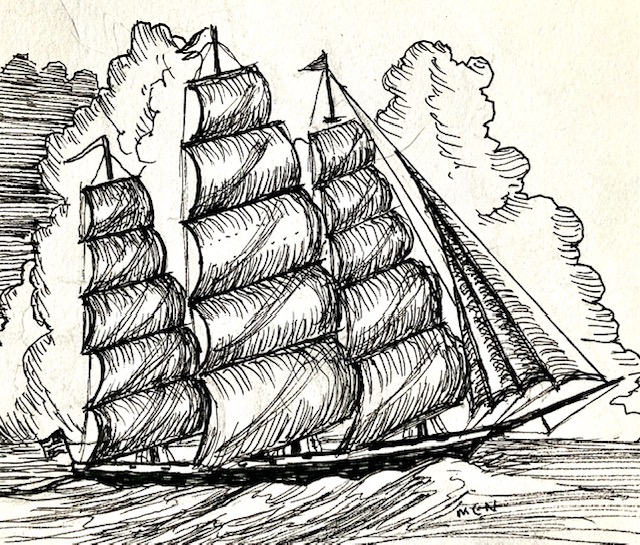

Here, Webb engaged in designing some of the fastest vessels in the world. His packets, sleek, speedy clipper ships, were high above the accepted mark for those times. Every craft was engineered for safety and speed. He also built some of the first steamboats and the largest wooden-hulled ironclad steamship, the USS Dunderberg. By 1843, William was building larger and faster ships such as the 900-ton Montezuma and Yorkshire and the prototypical clipper ship Cohota.

By 1849, he was pushing size boundaries by building the world’s largest merchant ships at almost 1,500 tons each. The California gold rush and increasing trade with the Far East kept up the demand for faster ships. In 1853, Webb’s shipyard produced what is considered the most beautiful clipper ship to ever sail the seas, Young America, and he didn’t stop there. In 1856, he built the largest ship ever to be built in his shipyard, the giant 2,145-ton packet ship Ocean Monarch.

Web did not ignore building other types of vessels, as he was a man who was always at the top of his nautical engineering game. He built many notable steamships, including the United States and Golden Gate, which was the first steamer to reach San Francisco. He built warships for Imperial Russia and for the newly unified Italy. During the Civil War, business in building commercial ships fell off, and the age of the “Ironclads” supplanted the types of boats his shipyard was building. No one had to tell William Webb that the age of the wooden sailing ship was at its end. Of course, some were still being built, but they were the exception and not the rule. William had made a fortune building ships, and now he looked forward to setting a new course for his life.

William H. Webb was not a man to just sit on his laurels. He invested in other businesses, including railroads and shipping lines in South America, and invested in New York real estate, which was booming after the Civil War, and built the Bristol Hotel at 42nd Street and 5th Ave., where I think the last “Tad’s Steak House” still operates. It was always the best place to go for a rubber T-Bone and dry-baked potato for three bucks when I was a kid. Now it’s $59.99 without a drink. Still quite a bargain on the New York restaurant scene.

But Willy was not done yet. It was at this time that Andrew Carnegie sold his steel company for more money than the worth of Trump and Elon combined. In today’s dollars. The old Andrew gave it ALL away to help build libraries, schools, and places for the arts to thrive. Carnegie did the unthinkable, and the super-rich “Grandees” in their new Fifth Ave mansions thought he was bonkers!

William H. Webb admired the thick-headed Scotsman who built his steel empire from nothing, and yet never forgot what it was like to be poor. So, he went “Bonkers” too. He helped reform the corrupt New York political system. Championed clean water for the city by chairing the Aqueduct Commission. And then turned his heart back to ships and the sea by building “The Webb Academy and Home for Shipbuilders.” The Academy furnished tuition-free education in the arts, science, and the profession of shipbuilding. Anyone with the will to be in shipbuilding, no matter how poor, went for free. The Home was a place for retired and forgotten shipbuilders to live and eat comfortably for free. He endowed this renowned institution with $2,000,000 (66 million in today’s dollars) so that it would always remain free as it does to this day. At present, it is now called “The Web Institute” as it continues on. Webb was also the founding member of “The Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers,” which has spread to every major shipbuilding port in the world.

Webb did not live to see the 20th century and all the advances in shipbuilding. He died two months before the new century arrived. He had lived a long, productive life. He lived as a compassionate humanitarian who loved ships, the sea, and those who worked on the waves. In 2018, William H. Webb was inducted into the National Sailing Hall of Fame.

Copyright 2025 By Mark C. (Sea) Nuccio

All rights reserved.

Send comments or curses to “mark@designedge.net”