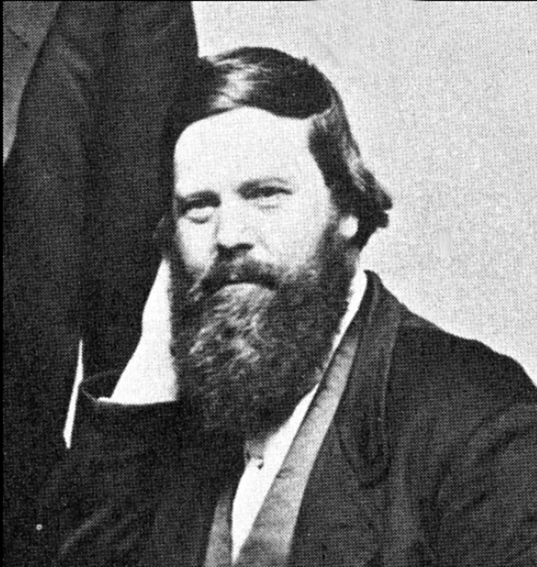

In 1873, Captain Sidney Buddington of Groton, Connecticut, took part in America’s first attempt to reach the North Pole. The expedition was led by the explorer Charles Francis Hall. Captain Budington came highly recommended as he was the nephew of Captain James Monroe, who, years earlier, had salvaged the famous ship Resolute from the Arctic and sailed it back to New London. But Budington would turn out to be at best a drunkard and at worst a suspect in the suspicious death of Hall. The Polaris Expedition was marred by insubordination, incompetence, and poor leadership.

Charles Francis Hall was a businessman from Cincinnati who became fascinated with Arctic exploration. Hall gained passage on the whaleship George Henry, commanded by Captain Sidney O. Budington out of New Bedford. They got as far as Baffin Island, where the George Henry was trapped by ice and they were forced to spend the winter. While there, Hall traveled with a local Inuit couple and found what he thought was evidence that some members of the lost Franklin Expedition were still alive. On his return to New York, Hall published his account of the expedition: Arctic Researches and Life Among the Esquimaux.

In 1863, Hall planned a second expedition seeking clues about the fate of the Franklin Expedition. During this second expedition to King William Island, Hall found remains and artifacts from the Franklin Expedition, but became convinced that no one had survived.

On July 31, 1868, a disturbing incident occurred that shows how emotionally unfit Hall was to be leading expeditions. Hall shot Patrick Coleman, an unarmed seaman and member of the expedition. Hall claimed that Coleman was attempting a mutiny. Other witnesses claimed that Hall was jealous of Coleman and angry that he was interviewing local Inuit without his permission. Coleman died two weeks later. Hall was never tried for Coleman’s murder.

On his third and final expedition in 1871, Hall was able to convince the US Congress to fund an expedition to try and be the first to reach the North Pole. The USS Polaris, a small steamer, was commanded by Hall’s old friend Captain Budington. The expedition was troubled from the start as the crew of twenty-five split into rival factions and discipline broke down.

On September 10, 1871, the Polaris sailed into Thank God Harbor in northern Greenland and anchored for the winter. Hall left the ship to explore and upon returning to the ship, he suddenly fell ill after drinking a cup of coffee. For the next week, he suffered from vomiting and delirium. During this time, he accused several of the ship’s company of poisoning him. Hall died on November 8th and was taken ashore and buried.

After Hall’s death, Captain Budington took command and organized an attempt to reach the North Pole in June 1872, but this was unsuccessful, and the Polaris turned south for home. On October 12th, in Smith Sound, the ship was beset by ice and was on the verge of being crushed. Nineteen of the crew and the Inuit guides abandoned the ship for the surrounding ice while fourteen remained aboard. The nineteen stranded on an ice floe drifted for six months and 1,800 miles before remarkably being rescued.

The damaged Polaris was run aground and wrecked by Budington near Etah, Greenland, in October 1872. Budington and his remaining crew managed to survive the winter and were finally rescued the following summer.

When news of the disastrous expedition and accusations of murder reached Washington, D.C., it led to a nationwide scandal, an official investigation, and accusations of a government cover-up. Suspicion fell mainly on German naturalist Emil Bessels, the expedition’s meteorologist. Bessels and Hall had argued throughout the expedition and Bessels was the only one who treated Hall upon his return to the ship. Being a scientist, he had access to the large quantities of arsenic carried aboard. At this time, arsenic was used as a medicine in small non-lethal doses.

The mystery of Hall’s death remained unsolved for nearly 100 years until 1968, when an expedition visited Hall’s frozen grave in northern Greenland. Because of the cold, dry climate, Hall’s body was remarkably well preserved. The expedition’s scientists took hair and fingernail samples, which were tested. They found that Hall had died of poisoning from large doses of arsenic.

Later in life, Bessels was involved in another suspicious death, this time of his fiancée. But no charges were ever brought. Recently, romantic letters written to a female sculptor, Vinnie Ream, by both Hall and Bessels have been found. Was Charles Hall murdered by Bessels out of jealousy? We may never know, but it certainly seems possible.