The California gold rush began in 1848 and people from all over the United States rushed to California in search of gold. Some traveled the difficult overland route, but many made the voyage on ships around Cape Horn to the West Coast. After dropping off passengers and goods the ships filled their empty holds for the return trip with guano. Guano is bird poop and was so valuable at that time that it was sometimes referred to as brown gold.

The guano rush started in 1804 after a German scientist brought a sample to Europe for analysis. Guano was rich in nitrogen and an incredible fertilizer. During the peak of the guano trade, particularly in the mid-19th century, hundreds of ships from various countries took part in transporting the guano. One of the captains in the trade was Connecticut native Charles W. Austin.

Captain Austin was born in Connecticut in 1820 and began his seafaring career when he turned eighteen. In 1842, he signed on as a boat steerer on the whaleship Charles Phelps’ first voyage out of Stonington, Connecticut. The Charles Phelps would later become famous under the name Progress for rescuing crews from a fleet of whaleships trapped by ice in the Alaskan Arctic.

The cargo from this successful voyage was worth $41,870, and Austin’s share as boat steerer came to $441.33, which is 77 cents a day. Three weeks after his return, Austin married Emma A. Bliven. They would have four children together. After his honeymoon, Austin shipped out again on the Charles Phelps’ second voyage. He became ill and was discharged at the port of Lahaina, in the Hawaiian Islands.

After recovering Austin shipped home and spent a short time working at the Potter Hill Mill in Westerly, Rhode Island. In 1853 he took command of the coasting schooner William H. Hazard sailing out of Westerly to New York and ports in the Gulf of Mexico. In 1858, Valentia was built and launched at Bath, Maine for the guano trade, and Austin took command.

For thousands of years, about fifty million seabirds had been nesting and pooping on the Chincha islands thirteen miles off the coast of Peru. Their poop, called guano by the Incas, accumulated to a depth of over two-hundred feet. Because it hardly ever rained on the islands the nitrogen in the guano never washed out, creating the richest fertilizer in the world.

Merchant ships, including many fine clipper ships, freighted the guano from the islands around the tip of South America to Europe and the United States. Guano’s value was so great that it led in1856 to the U.S. Congress passing The Guano Islands Act. This federal law enabled U.S. citizens to take possession of unclaimed islands containing guano deposits in the name of the United States. Hundreds of islands were claimed and a few remain U.S. territories including Midway Atoll and Johnston Island.

If there was ever a human endeavor that was both a curse and a blessing it was the guano trade. On the one hand, guano enriched soil and enabled farmers to grow far more crops to feed the world’s growing population. On the other hand, exposure to guano was extremely detrimental to human health. According to accounts, “You could smell the stench that came off the islands long before you could see them. Nothing grew on these islands, not a single plant. There was no water and the only living things were bats, scorpions, spiders, ticks, and biting flies.”

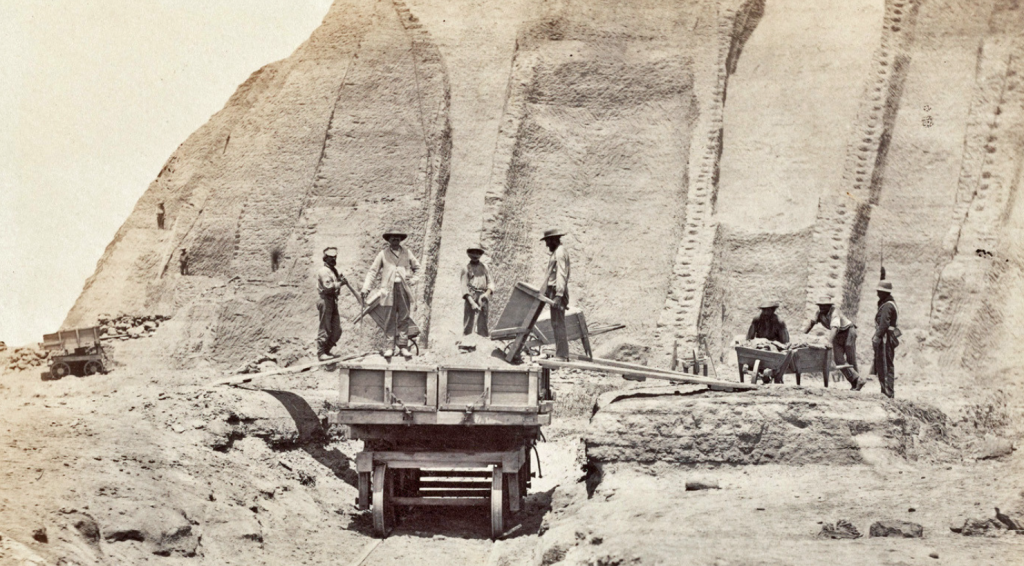

The mining of guano was a gruesome death sentence for the thousands of people who were forced to mine it. In the beginning guano mining was done by black slaves, but after Peru ended slavery another source of cheap labor was found. Starting around 1840 thousands of men were kidnapped from the Pacific islands and southern China and forced into slave labor. It’s estimated that as many as a quarter million Chinese indentured workers were shipped to the islands to live in virtual slavery until they died.

The noxious dust was detrimental to ships as well. When loading the guano into the holds the ships became covered in guano dust corroding the rigging, sails, and even metal fastenings. One ship almost sank rounding Cape Horn after the guano dust destroyed the ship’s pumps. The seamen had to bail for their lives with buckets.

In December of 1861, the Valentia was rounding Cape Horn with a cargo of guano bound for the United States when lookouts sighted a ship in distress. A tremendous gale was blowing, and it became apparent that the ship was not going to survive. The vessel was the Spanish brig, Nuevo Serafin. Using his years of experience Austin maneuvered the Valentia upwind of the floundering brig. It took three trips but all fifteen crew onboard the brig were rescued by the first mate and four brave seamen. The Valentia suffered damage and part of her cargo had to be thrown overboard. In 1862 Queen Isabella of Spain awarded Captain Austin a gold medal for his gallant service in the rescue of the Nuevo Serafin’s crew and the volunteers that manned the boat were awarded silver medals.

The guano trade began to decline as the guano on the islands was mined faster than the birds could re-produce it and ended when Fritz Haber, a German chemist, won the Nobel Prize in 1918 for inventing a process that could produce fertilizer artificially.

According to the Narragansett Weekly of September 1877, “Captain Charles W. Austin of Potter Hill, Rhode Island, a well-known man in this vicinity, died at his residence on Friday evening, Sept. 14th, after a long and painful illness. His funeral was held on Monday of this week and was attended by the Franklyn Lodge of Masons of this village. The body was carried to the Riverbend Cemetery for internment.”

Captain Austin was only 57 years old when he died, his obituary doesn’t say what the painful illness was that killed him. He’d been exposed to the guano dust when loading the Valentia for many years and guano carries a large variety of bacteria and diseases. I think we can speculate that his exposure to the toxic guano dust could have led to his death. Another victim of the curse of brown gold.