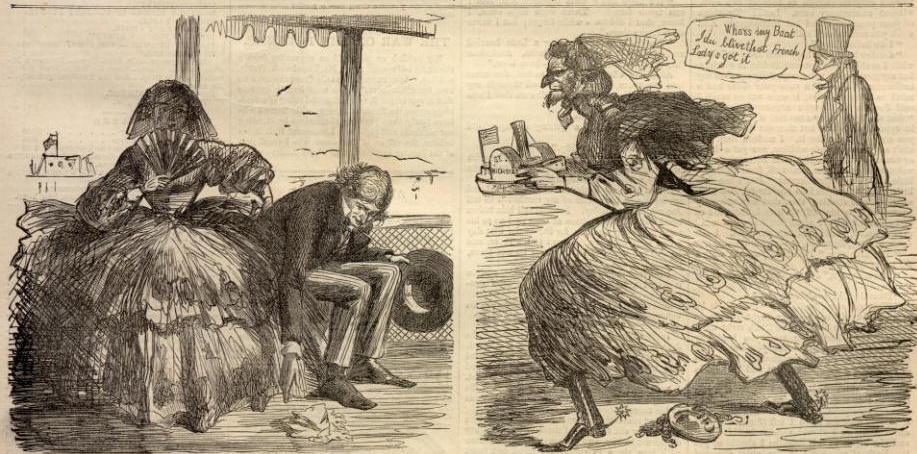

The passengers boarding the SS St Nicholas that warm evening at the Baltimore Wharf were relatively happy considering there was a civil war raging between the North and the South. Amidst the hustle and bustle of boarding some sixty passengers, there emerged an elegantly dressed French lady. Attended by a stern-looking man who identified himself as her brother. She was the topic of the conversation of both passengers and crew. Her name, Madame LeForte was stenciled on her half-dozen steamer trunks. The story that she was a French milliner about to open a dress shop circulated the decks. The purser was so impressed with the French lady he escorted her to the main deck stateroom, the best on the ship. Any skepticism of the authenticity of the French lady was put to rest when the captain, fluent in the language, declared she was truly French. Her broken English and fluency charmed all who encountered her. The French lady further charmed the men passengers who sought her attention; she used her fan as a coquettish invitation waving it in a seductive and flirtatious manner.

The steamer, St Nicholas, carried passengers from Baltimore to various ports along the Potomac River. The ship also carried supplies for the Union gunboat USS Pawnee whose assignment was to disrupt the movements of people and supplies to Confederate sympathizers from Maryland on down to Virginia. Unknown to the crew and passengers of the St Nicholas was the fact that Madame LaForte was neither French nor a lady. The cross-dressing charmer was Robert Thomas Jr. aka Richard Thomas Zarvona. An article in the Washington Times dated October 6, 2007, titled Rebel Raider disguised in a hoop skirt, describes him thusly, “Richard Thomas Jr. (his birth name) came from a notable Southern Maryland family. His father had been speaker of the Maryland House of Delegates and president of the Senate. An uncle had been governor. The Thomas estate, Mattapany, had once been the residence of Charles Calvert, the third Lord Baltimore and Lord Proprietor of Maryland. Thomas seems to have been born for adventure. He entered West Point at age 16, but his preference for martial arts instead of the civil engineering courses that dominated the curriculum led to his standing near the bottom of the first-year class. He resigned early in his second year. “It is believed that Thomas went west and worked for a time as a surveyor. From there he traveled to China where he fought pirates. He then went to Italy where he joined Giuseppe Garibaldi’s army during the Taiping Rebellion. Then engaged in fighting for Italian independence.

His family stories relate that he spent time in France where he learned to speak French fluently. In France, he served with the French Zouaves famous for their strict discipline, ability to fight, and unusual red pantaloon uniforms consisting of flared-out red pantaloons, blue doublets, crimson fezzes, and white gaiters. The members carried scimitar-like sabers. Thomas fell madly in love with a French girl named Zarvona. When she tragically drowned, he was heartbroken and, in her memory, changed his name to Richard Thomas Zarvona. By the time winds of the Civil War were blowing hard in May of 1861, Thomas was back in Maryland forming the core of what he planned to be a Confederate Zouave regiment. Thomas appealed to Virginia Governor John Letcher for financial assistance. At first, Governor Letcher was reluctant because Thomas impressed him as a very eccentric young man. But Letcher listened to Thomas’s plans and changed his mind. The plan was for Thomas to go to Baltimore and seek out Southern sympathizers. They would then board the steamship St Nicholas dressed as passengers. Thomas would be disguised as an elegant French Lady. Governor Letcher gave Thomas an advance of $1,000 to buy arms and to pay his co-conspirators. In addition, the governor contacted the Confederate Secretary of the Navy. The governor also promised Thomas a colonelcy if he succeeded and permitted him to use the rank during his escapades. George Watts, one of the Confederate raiders, became alarmed when he did not recognize Thomas. He was completely deceived by Thomas’s costume and imagined Thomas had missed boarding. He recalled “I was up on deck a-wondering where it was all going to end and whether I’d be hung as a Rebel spy when someone touched me on the arm. I wheeled around like somebody had stuck a knife in me and saw Alexander. He grinned…and said: “You’re wanted in the second cabin…. I hurried below decks and nearly had a fit when I found all our boys gathered around that frisky French lady. She looked at me when I came in, and, lordy, I knew those eyes in a minute! It was the Colonel.” (“Last Survivor of a Gallant Band “) The Evening Sun, Baltimore, August 27, 1910.

Around midnight the Confederates assembled in the French lady’s stateroom. SS St Nicholas had by then reached Point Lookout, at the confluence of the Chesapeake and the Potomac rivers. They opened the trunks which contained cutlasses, colt revolvers, and carbines. Thomas confronted the captain. Realizing he was outnumbered, the captain quickly surrendered to the Confederates. They changed the course of the SS St Nicholas and docked at the Coan River. Passengers were permitted to leave with all their possessions. While about thirty Confederate soldiers came aboard. The plan was to meet and capture the USS Pawnee but fate intervened. A Confederate sharpshooter had killed the Union captain of the USS Pawnee before it could meet the SS St Nicholas. The gunboat was ordered to return to Washington Naval Shipyard for the captain’s funeral. His plan was thwarted; Thomas decided to search for whatever ships he could find in Chesapeake Bay.

The first was the Monticello laden with coffee she was headed for Baltimore en route from Brazil. Thomas landed the 35,000 bags of coffee in Fredericksburg. Next was Mary Pierce. She was headed for Washington with a cargo of ice when captured by Thomas. Luckily for Thomas, his next prize was the schooner Margaret bound for Alexandria with a cargo of coal. The SS St Nicholas was by that time desperately in need of coal. Thomas sought safety in the Rappahannock River and towed the Margaret to Fredericksburg. He was met at the dock as a hero with cheering crowds. A ball was given in his honor. In Richmond, a parade was held in his honor.

Thomas was eager to get back to the business of raiding whatever ships he could find. Mary Washington was Thomas’s next target. However, another success for Thomas was not to be. Spies had learned of his plan and already aboard the Mary Washington were Union troops and the old crew of the SS St. Nicholas. Realizing he had been discovered, Thomas attempted to escape in a lifeboat but was captured before he could escape. Thomas and his Confederate force were captured and taken to Fort McHenry. Thomas managed to escape capture for a short time while still aboard the Mary Washington for a time with the help of a female Confederate passenger who stuffed him into a dresser draw.

An article “Last Survivor of a Gallant Band,” (The Evening Sun, Baltimore, August 27, 1910. (Relates the comment of George Watts who was one of the last survivors of Thomas’s band of Zouaves, Watts in 1910 was living above a Chinese laundry when a Baltimore newspaper reporter interviewed the seventy-eight-year-old veteran. Watt said that at first, he too had disliked and mistrusted Thomas, thinking that he “looked like one of [those] slick floorwalkers in a department store.” But Watts had a precipitous change of heart. “Believe me, sir that man had the quickest brain I ever ran across, and his eyes were just as quick. Eyes? Why, when that man looked at you it was like having an X-ray turned on you. It didn’t take us long to learn who was boss around there, so we got all our plans ready.”

After his capture, Thomas was held in solitary confinement in Fort McHenry. Despite the presence of his Zouave uniform and letter confirming that he was a Confederate Colonel on a commission from the volunteer forces of Virginia, he was held as a spy. Thomas was charged with piracy and treason. In December of 1861, Thomas was transferred to Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor. An entry in the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies records of the Civil War read as follows, “In April, Zarvona’s (Thomas) mother pleaded in a series of letters to Lieutenant Colonel Burke to permit her to visit her son in prison. At one point, her pleas were winning a favorable response. At the last moment, however, her requests were refused. On April 22, Burke received the following report: “At half past 9 o’clock last night Richard Thomas Zarvona, the French lady, a prisoner in close confinement at this post, informed the sergeant of the guard that he wanted to go to the water closet. The sergeant sent him out attended to by a member of the guard; when he reached the water closet (which is situated at the sea wall) instead of entering it he jumped overboard [into stormy waters] and attempted to escape by swimming to the Long Island shore. The guard immediately gave the alarm, and he was recaptured before he had succeeded in getting but a short distance. To prevent a reoccurrence of this, I have had a police tub placed in his room (Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies).”

The report states, ” Zarvona, unable to swim, had attached a belt of tin cans to his waist to keep him afloat. His efforts failed, and his confinement became more stringent than ever: he was not permitted to leave his casemate cell under any; circumstance and was constantly guarded by a sergeant known for his harshness (or three tough privates when the sergeant had to leave temporarily). Another request by Zarvona’s mother to visit her son was at first summarily refused. Then the refusal was rescinded, and Mrs. Richard Thomas visited Fort Lafayette: When he [Zarvona] came in [to the commander’s office] she did not recognize him at first, he was so changed. He looked so tall and was very thin and emaciated and had hardly the strength to speak. His hand, which you know was short and plump, is now long and bony. He held her hand all the time. She asked him how he was. He said he was as well as could be expected shut up without light or air, his cell partly underwater, with a place about the size of a dollar to admit the light; on cloudy days he could not see to walk about his room . . .” Correspondence from Captain George Thomas to General T. J. Stonewall Jackson, November 18, 1862, in which Thomas pleaded with Jackson to intercede. Zarvona (Thomas) continued to languish in solitary confinement. There were numerous requests for a prisoner exchange, but they were ignored. Word reached Virginia Governor Letcher that Thomas was being badly treated. Letcher threatened that he would place some Union prisoners in solitary confinement unless Thomas was released from solitary and exchanged. True to his word, Governor Letcher did indeed place some Union prisoners in solitary. Friends and relatives of those prisoners were outraged and made their feelings known. Eventually, Union Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton authorized Thomas’s exchange. On April 11th, 1863 Thomas’s exchange was ordered.

By that time, he had been moved to Fort Delaware. In poor mental and physical condition, Thomas returned to France in the hope of restoring his family’s fortune. He was unsuccessful then in 1872 he returned to Maryland. The following year he wrote his biography. According to a Washington Times article by Richard P. Cox (Rebel disguised in a hoop skirt) 2023. “He lived his last years in anguish over his health and declining finances. Thomas felt that his friends had abandoned him, and his gallantry had been forgotten Rich Thomas Zarvona died on March 17, 1875, and was buried on a family estate in St Mary’s County Maryland.